From himalmag.com

By Sunila Galappatti

The thought to create a collaborative journal at lockdownjournal.com

was spurred by the sudden closing of borders in March 2020 – a dramatic

shift that forced many of us to realise we had not truly imagined

lockdown until it was upon us. In my own household in Sri Lanka, we had

just decided it was time to confine ourselves, only days before our

government decided for us. We prepared (not very well) for ourselves and

for my parents who were poised either to return to Colombo on the last

regular flight or settle further into the home they’d made while working

in Dhaka, depending on which was more possible in the circumstances.

As we headed into physical isolation, I felt we were more conscious

than ever of our connections to each other across the world. In Sri

Lanka, the public first took real notice when a local tour guide caught

COVID-19 from a group of Italian tourists he had been showing around the

country. The spread of the virus itself spoke more intimately of our

interconnectedness than the platitudes or the shackles of globalisation.

When we spoke to friends in other parts of the world, we found shared

preoccupations. I had often bemoaned the geopolitical dispersal in these

conversations – for a change, it seemed we were all living in precisely

the same world.

The journal I set up was a minor attempt to reach across our closed

borders and record parallel experience, and in a very small way resist

our shrinking to national realities. Anyone, anywhere, could contribute

an account of a day lived in lockdown or during the continuing spread of

novel coronavirus. ‘Solidarity from at least two metres away’ reads the

tagline.

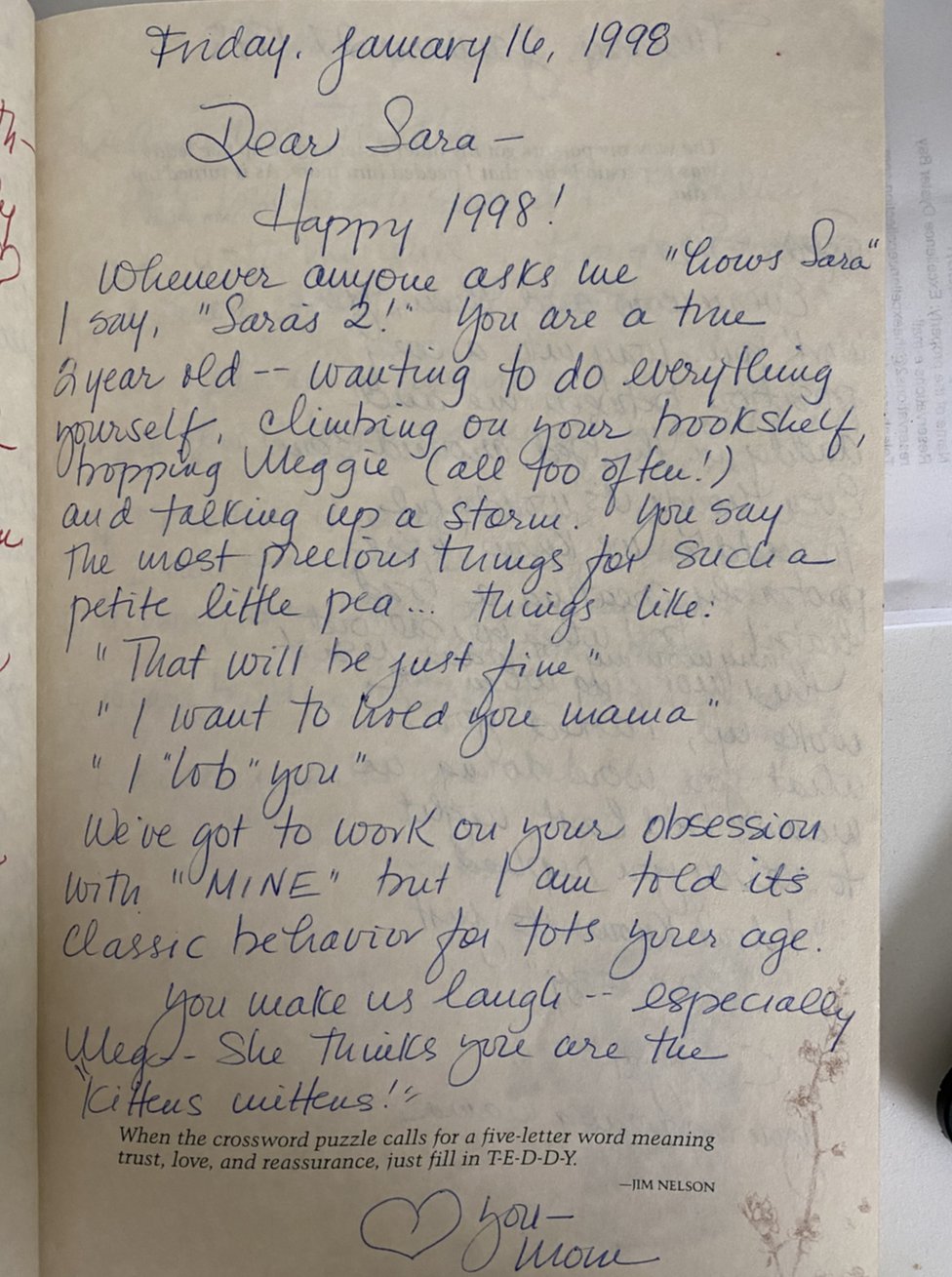

The idea seemed to me a cliché of the sort of thing we do online –

one might joke that we now even gather to write our diaries together,

unable to do anything at all without outward display. I was sure there

must already be many such repositories; indeed, I was a little surprised

to find that in mid-March 2020, the URL lockdownjournal.com

was still available. But here was a crisis that was actually new to most

of us and one craved a longer, quieter form to reflect on it than

breaking news or social media feeds would allow – a chance to think in

days rather than moments.

I did the obligatory rounds of second-guessing. We could not possibly

create a detailed chronicle of a time. By necessity, those who would

contribute would only be those who had the spare time, resources and

mental space to do so – to say nothing of online access, easy literacy

and the option to express themselves in English. We would be writing

about a pandemic from which we weren’t suffering acutely – it was

unlikely the sick would be keeping a diary, much less the carers,

front-line medical staff, daily wage earners without work, stranded

migrants, the ‘illegal’ stateless or refugees in worsened camp

conditions. Would the journal become a repository of bourgeois minutiae

from across the globe? My anxiety was in part that self-defeating,

oversimplifying, contemporary fear of the fragment – we do everything in

the knowledge that someone will point out that we are not

representative enough. But it was also a purer fear of ourselves and

what we have become. Would we, the privileged, be exposing ourselves? In

fact, this second question tempted me. I drove through my hesitation

for the sake of a possibility we might paint pictures of our lives

without being able to anticipate how we would look back on them. We

might tell a story we could only understand later. When I reflect on

these impulses now, I wonder if I dared to hope the world would change

more quickly than it has.

Entries began arriving immediately, initially in response to a test

balloon sent up on social media and before I had even configured the

journal site. Within a week, I began to receive accounts from total

strangers, beyond the interconnecting circles of friends of friends. It

was not surprising that articles about the journal in The Hindu and Firstpost

should expand the network of contribution, especially from Indian and

Southasian diasporas around the world. But asking contributors where

they heard about the site, I was struck to find, for example, that a

number could apparently be traced to a pair of posts on Facebook and

LinkedIn by the British Psychotherapy Foundation (to which I have no

known connection). Of course, news itself spreads along hidden lines of

close contact. Over eight months the site has gathered over 200 entries

by close to 75 different writers. They came from Argentina, Australia,

Austria, Brunei, Bangladesh, Germany, India, Jamaica, Jordan, Kashmir,

Kenya, Mauritius, Namibia, New Zealand, Nigeria, Peru, Portugal, Sri

Lanka, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the

United States.

Looking back at the entries now, I see they begin anxiously. They

show how little we knew in March about the virus, how unknown the

bogeyman. A BBC journalist on his way to work in London, deemed an

essential worker, is acutely conscious of space: how he and two women

walking towards him will share the pavement, whether the guards at New

Broadcasting House have enough space, how a huddle of homeless people

are gathered together by necessity. A woman over 70 is disoriented by

her classification as a vulnerable person: Will the neighbours

report me to the police when I get in my car or walk out to see the

sunset? The young shop assistant said I didn’t look 70. How absurd to be

so ridiculously pleased.

At this point, everyone, everywhere, is checking case numbers. A

Kashmiri doctor records the chaos and stigma in a ward of the hospital

where she works in Dhaka, following first suspicion of a COVID-19

positive patient. Another Kashmiri woman, this time in Bangalore,

reports on 22 March: After 9pm, when the Janata curfew ended people

started to show up at our house or on the roads. Almost everyone who

comes here or calls asks, ‘How did you Kashmiris survive the lockdown

for six months?’ I shrug my shoulders. The gesture is defensive but

the journal is full of people worrying about the places they are from

but may not live in, or places in which other people live whom they love

– a map of geographical intimacies.

Instantly – even in March – the effects of lockdown, rather than the

virus itself, tell in people’s personal lives. A wedding cannot take

place as planned, grandparents are not able to meet their new-born

grandchildren, and people who find themselves in different countries

from their partners, holding different passports, face up to the

prospect of prolonged separation. It seems that across the world people

are already facing disruption to the previously accepted essentials of

personal life, and doing so with an equanimity usually known only to

people and places in explicit conflict. But on 2 April, an introverted

software engineer in Bangalore finds that a postponed wedding also

allows him and his fiancée a little more time to get to know each other,

over the phone, before the wedding:

Night falls and I talk to her. Did I

mention she is also an introvert? That we both have difficulty keeping

up a conversation? Although we have come a long way since we first met

in October 2019, we still find difficulty in talking about things.

Sometimes we let the silence take the driving seat. Sometimes we hit on

something that just takes us till morning. And sometimes we say

something so beautiful that waking up next day does not feel tiring or

frustrating or, dare I say, lonely.

There are recurring concerns in entries, especially in the

anticipation of prolonged lockdown – it seems the young everywhere are

worried for their elders (so much for clichés to the contrary). It goes

without saying that we are all preoccupied with food: the sourcing,

substitution and cooking of what can be found. Of course, all of this

takes place at the least urgent or inconvenienced end of the spectrum of

need; that fortunate state in which we cook for literal sustenance but

also as a process through which to calm, pace, nurture and entertain

ourselves. Just as inevitably, many contributors are also preoccupied

with parenting their children, without school, reprieve or access to the

outdoors – in this case, parenting as a process through which we

question, doubt, fail and disintegrate.

One contributor commented on the role that the journal itself played

in his early lockdown days: he said that reading it was something to

look forward to, a note added to life at a moment when the tendency was

for things to be taken away. He said he also welcomed the warming of a

locked down, self-absorbed world with accounts of other people’s days

from elsewhere on the planet. Indeed, it is a rarity, pandemic or no

pandemic, that we have a chance to chart the rhythm of a whole day lived

by another person.

This still does not explain why people wrote to the journal.

Was it precisely for solidarity? Did they have more time than usual or

were they in fact more pressed? More than one contributor mentioned in a

note accompanying a submission that they were writing while their

children slept or stealing time from precious working hours – suggesting

that what the journal offered them was a quiet place to retreat and

reflect.

I used to teach a cabinet-of-curiosities class on the journal form;

in it I would use James Boswell’s London journals of 1762-1763 to

illustrate self-conscious performativity and Virginia Woolf’s wry

entries on the end of World War I in her own journals, to debate the

uses of personal impressionistic accounts in helping us to look back on

historical moments. Woolf’s entry for 11 November 1918 begins

“Twentyfive minutes ago the guns went off announcing peace” – over that

day and the next, she paints a vivid picture but does so from a high

altitude, the account coloured in with class prejudice. If I am forced

to identify an intention for the Lockdown Journal, it probably

was to spark this form of revelation in which we reveal more to the

reader than we can necessarily see ourselves. Except that in the case of

a collaborative journal, there is a dynamic exchange of roles between

writer and reader, both understanding more and searching further as

entries accumulate.

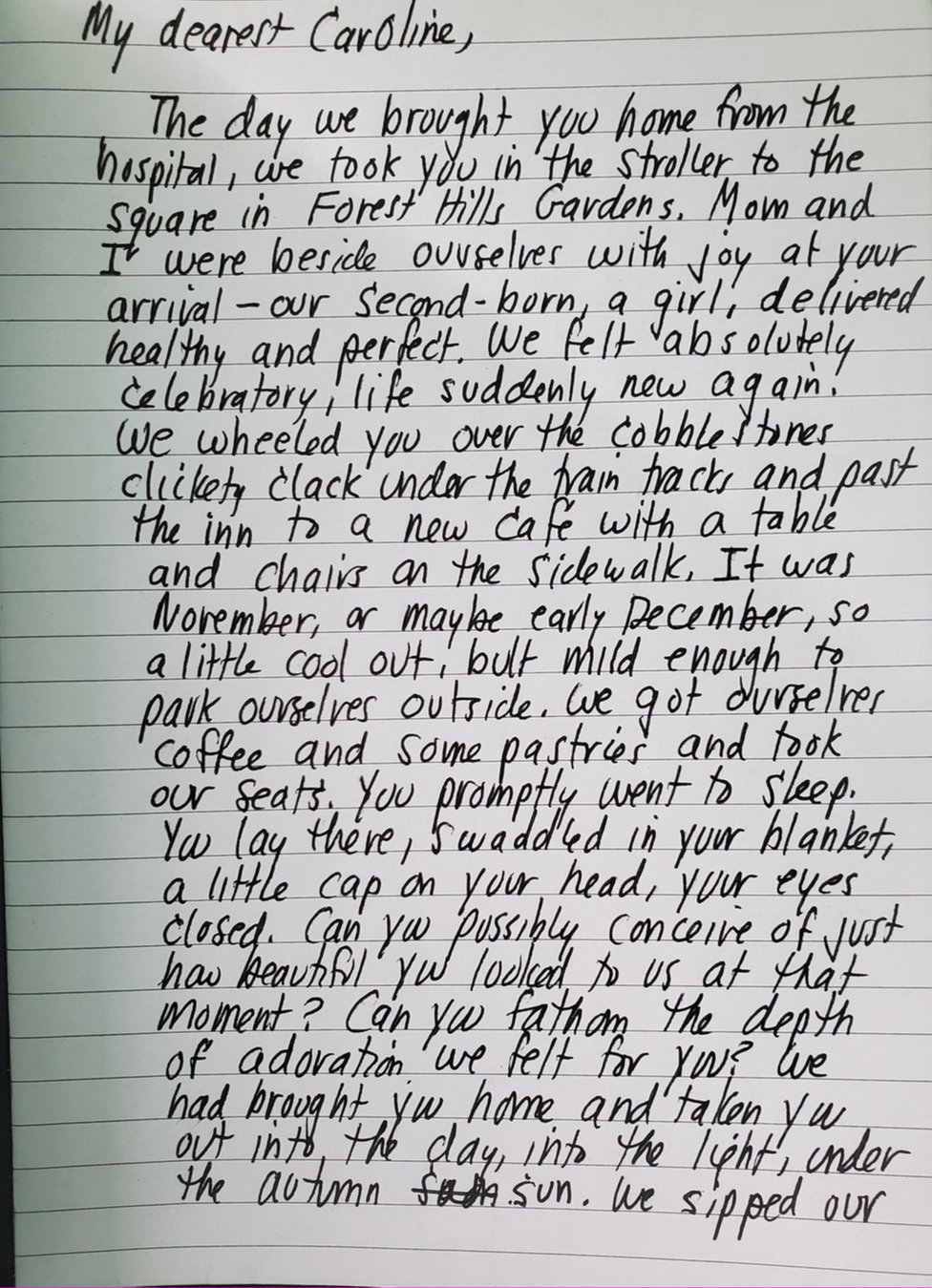

The submission guidelines for the site offer an apology that selection

will be subjective: that self-consciously literary efforts may be turned

down, that preaching, activism and performative blessing-counting are

discouraged and that the barometer will be whether the editor deems a

piece bearable to inflict on a reader. But, despite the bossiness of

these guidelines, I am wary of claiming a precise or grandiose

intention: the instinct to start the journal was also influenced by a

small diary I found a few years ago, written in pencil on a child’s pink

stationery (Japanese-made kitsch, the height of luxury in 1980s Sri

Lanka and lovingly reserved for special occasions). I had written it as

part of a homework assignment set the last time schools here were closed

for as extended a period as they are now (during the Beeshanaya / JVP

insurrection of 1987-1989). The banal listing of activities by a

middle-class Colombo nine-year-old turn out to be more interesting now

than one might have expected, especially in relation to a conflict of

inequalities — a tiny fragment of a moment.

Time extends in the Lockdown Journal and a woman leaves a

bowl of soup for her COVID-19 positive neighbour. Another is angry at

the lack of COVID-19 protocols at local council elections in Queensland

Australia. On 7 April, there occurs a painful symmetry of pieces. In

Modinagar, India, a young man writes of his friend who has been sent to

quarantine along with others in his hostel, all Muslim, because

neighbours have raised suspicion of a ‘corona jihadi’ in their midst.

The very same day, a woman in Sri Lanka finds she can’t concentrate on

the chores she’s set herself:

The Prime Minister had made a speech

last night that I only heard today. In that speech, all two million

Muslims in Sri Lanka were told to forget about their burial rights. This

was not the time to ask for respect of religious laws, we were told; it

was the time to come together as a country. Today, therefore, is

another day where I can do nothing. The weight is heavier than it has

been and I do what I can to function. I pace my living room, forgetting

my plans to clean.

Reading this early April entry again, I realise that one positive

facilitated by lockdown was the intrusion of the personal – whether in

the form of children butting into Zoom meetings or this ability to trace

political mood through our most minute domestic rituals. The journal

form also permits the weaving of public and political consciousness

through the most mundane – and essential – tasks of getting a family

through a day. Having to clean one’s house is not a matter to be

discounted (or palmed off on underpaid domestic workers) it is another

thing that has definitely to be done. So it matters that it is disrupted

by violent and bigoted politics in the public sphere. I wonder if this

is why people have written to me repeatedly over recent months to say

that the Lockdown Journal offered them an alternative to the news – a

compensation that troubled me slightly at first, given the distance

between the two forms.

Perhaps what they meant was that the journal revealed news differently

to them, and at a gentler pace – for example when a public servant in

Canberra, Australia, wonders how the ‘essential’ government services he

performs will be reconceived in a coming exigency or a doctor in

Pennsylvania, USA, drives two hours to buy a box of masks, still in

short supply. This particular box, she will keep to protect her family,

she writes, in case a time comes when she gets sick. The flimsy

reassurance of a box of masks in a bathroom cabinet offers us a brief

glimpse of professional and personal anxiety closer to the front-line.

Towards the end of April, the first personally-known COVID-19 death,

though not the first death, is mourned in the journal. Around the same

time a woman faces the isolation and elongation of everyday

heart-breaking loss, due to the pandemic, needing to attend alone an

appointment where she discovers the baby she is carrying has stopped

growing. She writes:

As the doctor ran me through my

options, I realised that in the last hour I had spoken to more people in

person than I had in weeks…By the time I left the hospital this number

had grown considerably: the receptionist who checked me in; the two

nurses in the scanning room; the nurse from the fertility unit who came

by to see how I was; the doctor who was so kind to me; the pharmacist

who saw my prescription and told me that everything would be ok; the

nurse outside the pharmacy who saw me weeping and got me a cup of tea.

Essential workers doing essential work, god bless them.

Throughout this account there is an attention to the detail of

others’ inconveniences that is admirable in the circumstances – among

them are nurses who want to offer a hug but can hardly give a

satisfactory one in full PPE (personal protective equipment), even if it

were allowed in a pandemic.

Indeed, more of the world begins to register in the journal around the

end of April – in part due to an easing of restrictions in some places.

The writers of the journal begin to test out the world again, with

altered eyes. A woman in Berlin receives a manual from a friend on how

to wear a mask properly. In the same entry, she looks up at the sky and

notes there are no planes in it. For our doctor in Pennsylvania, or

rather for her patients, things have intensified. She rings a family to

confirm a positive COVID-19 result. She says:

In our neighborhood, many families

are a few paychecks away from being poor. They look like me, but our

lives are very different. Their labor makes fresh bread, pints of

blueberries, summer corn, and garlicky dumplings cheaper for the rest of

us. For the past two months, society has called them ‘essential’. But

this hasn’t led to higher wages or better working conditions. Instead,

being essential has led to infection. And fear. Once a worker gets sick,

it’s hard to keep the virus from spreading inside small homes. Today,

the family’s fear is focused on the children in the household. We talk

for a long time.

Afterwards, I struggle with anger and

a jittery kind of anxiety. Two months into lockdown, why aren’t my

patients safe at work? We know it’s possible. We take precautions at the

clinic, and we’ve been successful so far. Why are my patients

‘essential’ only until they fall ill?

Towards the end of May, accounts begin to diverge and tense – life

gets more complicated, in fact, when many of us move from total lockdown

toward uncertain approximations of normal. A father violates the rules

against crossing state lines, to ensure that his children have access to

both their parents during this time. He tries to stay positive, pulling

against a tide of discontent within himself about the ways our

establishments have arranged and neglected their responsibilities to the

public. His grief is heightened by the particular time and place in

which he finds himself – for this is America, days after George Floyd

was murdered by Minneapolis police. At the same moment, in Kolkata, a

woman writes of her octogenarian neighbour trying to locate the

building’s electrician after Cyclone Amphan has left her in darkness. In

Los Angeles, a couple put their children to bed before they turn on the TV and watch the city burn.

In early June, a woman wakes at 2.30 am in Mount Lavinia, Sri Lanka,

and finds her teenage son wide awake, reading and doing push-ups. He is

pleasantly surprised that instead of shooing him back to bed, she offers

to make them both a hot drink. She asks him how many other people he

thinks are doing the same in the dead of night. He answers, plenty of people.

In fact, the journal does seem to point to strange symmetries of mood

among the comfortable of the Earth. At one point, everyone, everywhere,

has a bad week. At another, a stream of people take their first

holidays since the pandemic began, driving out to escape the tension and

pressured uncertainty of everyday life. These symmetries are

characteristics of privilege, no question; indeed, the journal is full

of caveats and acknowledgments. One sometimes wonders if our heightened

contemporary awareness of privilege helps us avoid actually addressing

inequalities. Yet I have come to appreciate the journal for the very

particularity I originally feared – the minor courage of people willing

to tell minor truths about themselves.

The story of gradual release is already reversed – at the time of

writing, cases in India have passed the 8.5 million mark, several

European countries have returned to lockdown, and even as the US

presidential election is hailed hopefully as a global bellwether,

authoritarianism strengthens its grip worldwide. Submissions to the

journal have naturally slowed as people become more accustomed to newer

realities, have less time and face more concrete challenges than at the

very beginning of the crisis. The pandemic has ceased now to be an idea,

its novelty worn off. But this is precisely where the story threatens

to get more interesting, if we can keep telling it. The Lockdown Journal remains open to submissions indefinitely.

https://www.himalmag.com/brief-history-of-moments-indoors-pandemic-issue-2020/