From timesofisrael.com

Unearthed journals reveal how the Jewish novelist who died by suicide in 1942 foresaw ‘dangerous, embattled times’ in the 1930s, his mental health declining with Hitler’s advance

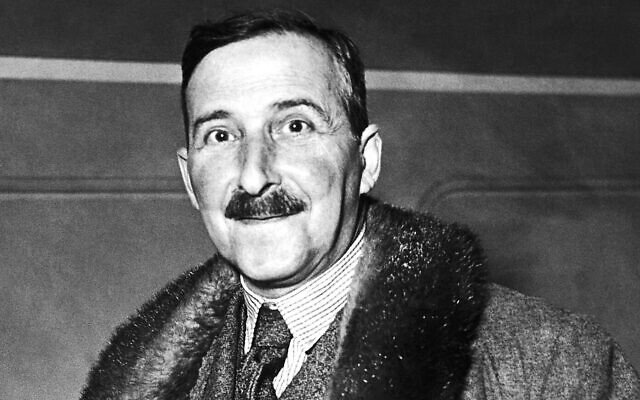

LONDON — “I have just decided to resume keeping a diary after a many-year lapse,” begins Stefan Zweig’s entry for Thursday, October 22, 1931. “My motivation for doing so stems from my premonition that we are heading towards dangerous, embattled times that would be a good idea to record.”

While the Austrian Jewish literary giant — one of Europe’s most popular interwar writers — did not foresee the scale of the catastrophe ahead, Zweig’s fear of the rise of fascism proved chillingly accurate. That fear, moreover, hangs over his diaries of the period, which have recently been released for the first time in English.

“Diaries 1931-1940” throws a fascinating light not just on Zweig’s deepening sense of foreboding about the slide towards nationalism and authoritarianism, but also his professional and personal insecurities, and active social life.

A novelist, playwright and essayist, Zweig’s works include biographies and studies of Marie Antoinette, Charles Dickens and Honoré de Balzac, as well as the novellas “Letter from an Unknown Woman,” “Amok” and “Fear.”

Perhaps the diaries’ darkest passages, which appear to foretell the novelist’s suicide in Brazil in 1942, are those Zweig wrote in the UK during the spring and early summer of 1940 as the Nazis swept through France and the Low Countries and an invasion of Britain appeared imminent.

“If the Germans invade after the fall of France, I don’t want to fall into their hands alive; I am very aware of what would happen in such a circumstance,” he confides to his diary on June 2, 1940. “Back in my youth… I could never have imagined that closing in on my sixtieth birthday I would end up being hunted down like a criminal.”

Nor were these fleeting feelings. A week later, as the German advance in France continued, Zweig writes: “I don’t want to go on anymore: I only hesitate regarding how to impose that decision.” When he contemplated the Nazis installing the British fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley at the head of a post-invasion puppet government, Zweig — who, had already written of his relief to have “a special little vial ready in case what I’ve foreseen happens” — again returned to thoughts of suicide. “Our life has now been destroyed for many decades to come and I don’t have many decades left; I don’t want to have them.”

Indeed, one of the diary’s last entries contains the words: “There is chilling news: the swastika is flying from the Eiffel Tower! Hitler’s troops are standing guard at the Arc de Triomphe! Life is not worth living. I am almost 59 and the coming years will be terrible: why suffer through so much humiliation.”

Even with the full horror of the Nazis’ attempts to annihilate European Jewry yet to unfold, Zweig’s fears about his fate after a German invasion were by no means unfounded. Appalled by the growth of national socialism in his native Austria, Zweig went into exile in Britain in 1934, but he remained on the Nazis’ radar: his books were banned, citizenship revoked and his name and address in London entered into the notorious “Black Book” — a hit list of prominent Britons and refugees whom the SS intended to round up after it occupied the UK.

Zweig kept private notes and diaries intermittently throughout his life. However, they did not come to light for more than four decades after his death when they were published in Germany in 1984. The new publication, which contains entries for 1931, 1935, 1936, 1939 and 1940, will be joined later this year by diaries for the years 1912-1914. Publisher Ediciones 98 will subsequently release two further volumes covering World War I.

The diaries, says editor Jesús Blázquez, “allow us to learn about Stefan Zweig’s work and authentic opinions in a new and different way, from very private, sincere notes expressing his true feelings and revealing very personal matters.”

“He was writing for himself only, with no intention to publish, and was therefore unhampered by concerns over acceptability or the ultimate consequences of his writing,” Blázquez says.

A grim future

Zweig’s pessimism about the fascist threat is evident from the outset of his 1931 diary. “The political panorama looks grim,” he writes in October 1931. And, referring to the armed far-right militia formed shortly after WWI: “The Heimwehr acting out in the open worries me. It is all causing me to become obsessed with finding a temporary refuge.” Days later, as the economic crisis worsened, Zweig penned: “I am sure there’s another coup brewing, and I think it will be successful.”

On a trip from Paris to London four years later — by which time he had fled Austria and Hitler was installed in power — Zweig’s apprehensions about the future had grown. “Each new day we are more prepared for a new cataclysm, always feeling that low underground rumble in our hearts,” he notes. “We are constantly seeing the straight being made crooked and the plain being made rough. It’s as if a drunken madman has taken hold of the world’s rudder and is sending us zigzagging into the abyss.”

A false reprieve

By September 1939, Zweig’s decade-long sense of dread was about to be realized, although he initially appeared to find Britain a reassuring berth. Bath, the English city to which Zweig and his second wife, Lotte Altman, had moved earlier in the summer, was “not at all changed” by the impending outbreak of war. “Nobody hurries or seems excited; everything goes smoothly,” he notes. As the eight-month Phoney War ensued, Zweig’s admiration for the British appears to swell. “[T]he people are wonderful, the preparations seem to be perfect, the activity of this country, which is strong through [its] unity, is really overwhelming,” he writes.

But Zweig also complains of the frustration of no longer being able to write and be published in his mother tongue. What “oppresses [me] most,” he notes in sections of the diary which, unlike earlier entries, are written in English, is that “I am so imprisoned in a language which I cannot use.” When his friend Sigmund Freud dies in London in late September 1939, Zweig writes: “I feel again my isolation in this country — I have no newspapers to write a few words, no opportunity to… say something and this after six years in England.”

As he awaits naturalization and British citizenship — it eventually comes in March 1940 — Zweig also writes of the “humiliation” of being officially classed as an “enemy alien” in the UK (he objects in particular to thus being implicitly designated as a German, believing that amounted to a tacit recognition of the annexation of Austria). Restrictions imposed on Germans and Austrians living in Britain at the outbreak of the war — such as having to report to the police on their travel plans — were “a shame [at] my age and in my position,” he writes. “My situation here is disgusting — isolated, without power and opportunity to express myself,” he complains in a later entry.

Storm of war

It is, however, the wider course of the war itself which dominates Zweig’s diary entries. From the outset, he is pessimistic about England’s prospects, fearful both of a Nazi victory and the human cost of fighting the war. “I cannot see how Germany can be defeated nor how England or even France can be broken,” he writes four days after the war’s outbreak. “I do not dare to hope that reason will still prevail and the war stopped before the real excitement begins.”

When the Soviets join the Nazis in carving up Poland in mid-September 1939, Zweig focuses his ire on British prime minister Neville Chamberlain who, he says, had frustrated prospects of an anti-Nazi alliance with the Russians. “The war from this moment on is a nearly… impossible struggle,” he states. “Never [has] a great power… been so annihilated by the stupidity of her leaders.”

As the Phoney War ends and the German Blitzkrieg begins in May 1940, Zweig’s mood darkens further. “We are now having the worst days of our lives. Once again, world history takes a new dramatic turn.” News that the Germans have occupied Amiens and could soon reach Abbeville and the Channel coast “took my breath away,” he writes. “This is a catastrophe.”

“For the first time we are sensing danger up close. I don’t think even an enemy landing can be ruled out… coming face to face with the Germans, after fleeing them for seven years, would be awful,” Zweig writes days later as Boulogne falls and the Nazis race towards Calais.

Zweig does not, though, view Hitler’s apparent imminent victory simply through a personal lens. “To think that this liar is the master of the world,” he writes as Poland is dismembered. “Hitler’s most heinous crime,” he notes the following spring, “will be to have raised lies and fraud to a position of respectability, while now defining what has been judged criminal during Millenia as the art of governing and living.”

‘A great surge of energy’

While Zweig cheers Winston Churchill’s arrival in Downing Street — the new prime minister “quickly injected a great surge of energy into the country” — he questions whether England should fight on alone.

“I do not underestimate the English resilience, it is magnificent, but it would be extremely dangerous to prolong the fight over an acute sense of honour, as that would only lengthen the conflict not win it,” writes Zweig.

Surveying the bleak military situation — the Channel blockaded, the evacuation of British forces from Dunkirk underway and “not a whisper of encouragement from America” — Zweig concludes: “There’s no possibility of any true counter-attack.” Two weeks later, in mid-June 1940, he expresses his belief that “from now on I think individuals will be sacrificed in pursuit of impossible victory; in contrast defeat [of Germany] is totally inconceivable.”

Collapse

Against this backdrop, Zweig sinks into depression and despair. “I am barely able to think, my feelings are making me sick and I feel about to collapse,” he writes as he contemplates the kind of “peace” Hitler might impose on Britain. “This situation is paralyzing me; as horrible as it is, it’s only going to get worse,” he adds. The fall of France — “the most adorable country in Europe” — leads Zweig to ask: “Who is there to write for, what is there to live for?”

“In this section his diary entries on the war are a bit contradictory, reflecting his overwrought mental state resulting from the advance of Nazism,” says Blázquez. “These feelings increased his pessimistic view of the conflict, and his lack of confidence in an Allied victory drove him to adopt a defeatist attitude and, at his lowest moments, to believe that keeping up the fight against Germany would only be a senseless waste of lives.”

Alongside his fear of a German invasion, Zweig is also acutely conscious of growing tension in Britain as the government orders the internment of “enemy aliens.” Although he has now been naturalized and thus escapes detention, he believes he is perceived as both “a bothersome outsider, a person still requiring caution” or even “the enemy.” “The distrust is discernible and will end up as hate,” he writes. “[T]he tenacity of the English will erode their good nature.”

But although Zweig ultimately decides to leave the UK for Brazil, he repeatedly debates the merits of taking refuge in another country and starting afresh. “I still see no country to which I would really want to go. I feel too exhausted to pick up everything and emigrate,” he writes in May 1940. Days later, he returns again to the topic. “I don’t know what to decide! I must let the dice fall as they may, as any overt act of will on my part would make me responsible for everything.”

Painful pinnacle

Ultimately, his fear of his fate should the Nazis invade Britain led Zweig — after a few frantic days in London obtaining the necessary paperwork — to set sail for New York from Liverpool on June 25, 1940. After a month in the United States, Zweig and his wife disembarked in Rio de Janeiro in late August.

While they provide a window into Zweig’s troubled state of mind, the diaries, believes Blázquez, also show the novelist reaching “maturity both as a person and as a writer.” f his best work,” Blázquez says, noting that the diaries “contain interesting details of his working method and how he constructed his works ‘Maríe Antoinette,’ ‘Balzac’ and the English edition of ‘Decisive Moments in History.’” The diaries also show him beginning to think ahead to his posthumously published autobiography, “The World of Yesterday.”

“During this decade he produced some of his best work,” Blázquez says, noting that the diaries “contain interesting details of his working method and how he constructed his works ‘Maríe Antoinette,’ ‘Balzac’ and the English edition of ‘Decisive Moments in History.’” The diaries also show him beginning to think ahead to his posthumously published autobiography, “The World of Yesterday.”

Despite his undoubted professional success — over the course of two days in August 1936, for instance, over 3,000 people turned out to hear Zweig speak during a visit to Rio — the diaries also reveal Zweig’s profound insecurities. After a visit to New York in January 1935, the novelist notes his “growing fear of all types of public events.” Even smaller gatherings appear to make him anxious. “My inability to speak with people around a large table increases,” he writes. “I lack the aptitude for and the interest in social life.”

Nonetheless, the diaries are littered with references to Zweig’s active social life, with visits to cafes, restaurants and the theater interspersed with “sumptuous” dinner parties. When he sails to America in 1935, Zweig travels with his friend Arturo Toscanini and later joins the composer’s wife and legendary New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia (“looks like an Italian bartender,” the novelist notes) in a box for a concert.

The diaries also detail Zweig’s relationship with the composer Richard Strauss — “that hearty, ruddy-faced good-natured Bavarian.” Strauss later defied the Nazis and refused to remove his librettist’s name from the program when “The Silent Woman” received its premiere in Dresden in 1935. (It was banned after three performances when the Gestapo intercepted a letter from Strauss to Zweig which was critical of the regime). Soon after, Strauss was made to quit his post as Reichsmusikkammer president.

The playwright Gerhart Hauptmann, of whom Zweig writes in 1931 “one perceives timidity, a sweet nature and goodness in his gaze,” proved rather more willing to accommodate himself to the Nazis. The former socialist’s decision to remain living and working in the Third Reich was, in turn, ruthlessly exploited by the Nazis for its propaganda value.

For Zweig, as a Jew, no such accommodation was offered or accepted. Instead, the Nazis forced him into exile, hastened his death and, he believed, robbed him of the language in which he wrote the novels and plays which had won him such popularity and acclaim around the world.