From salon.com

By Paula Vene Smith

Handwritten diaries and digital diaries both help preserve experiences and memories, but in different ways

he first time I taught a college course called "The London Diary" for young Americans studying abroad back in 2002, each student ended up with a tangible book of memories, a handwritten record of their semester in London. But when I taught the course 15 years later, the first question my students asked was whether they could keep their journals online. The question brought home to me how the image of a diary has shifted from words scribbled in a blank book to images and digital text on a screen.

Why not go digital?

Even while journaling apps like Penzu and Diaro become more widely available, estimates and surveys suggest that a sizable number of the world's diary keepers still keep handwritten diaries.

Fans of digital diaries grant them an edge in convenience, portability, searchability and password protection. Jonathan, one of my 2018 students, described in an essay for class how digital diarists can upload entries to multiple platforms, keeping some portions offline or restricted to a select audience while other parts go completely public. It's harder to control distribution, encrypt entries or build an index with a journal kept on paper.

I already expected my students to use electronic devices to read course materials, to communicate with me and with their families back home, to write essays for class, and to navigate London. Why not let them keep digital diaries, too?

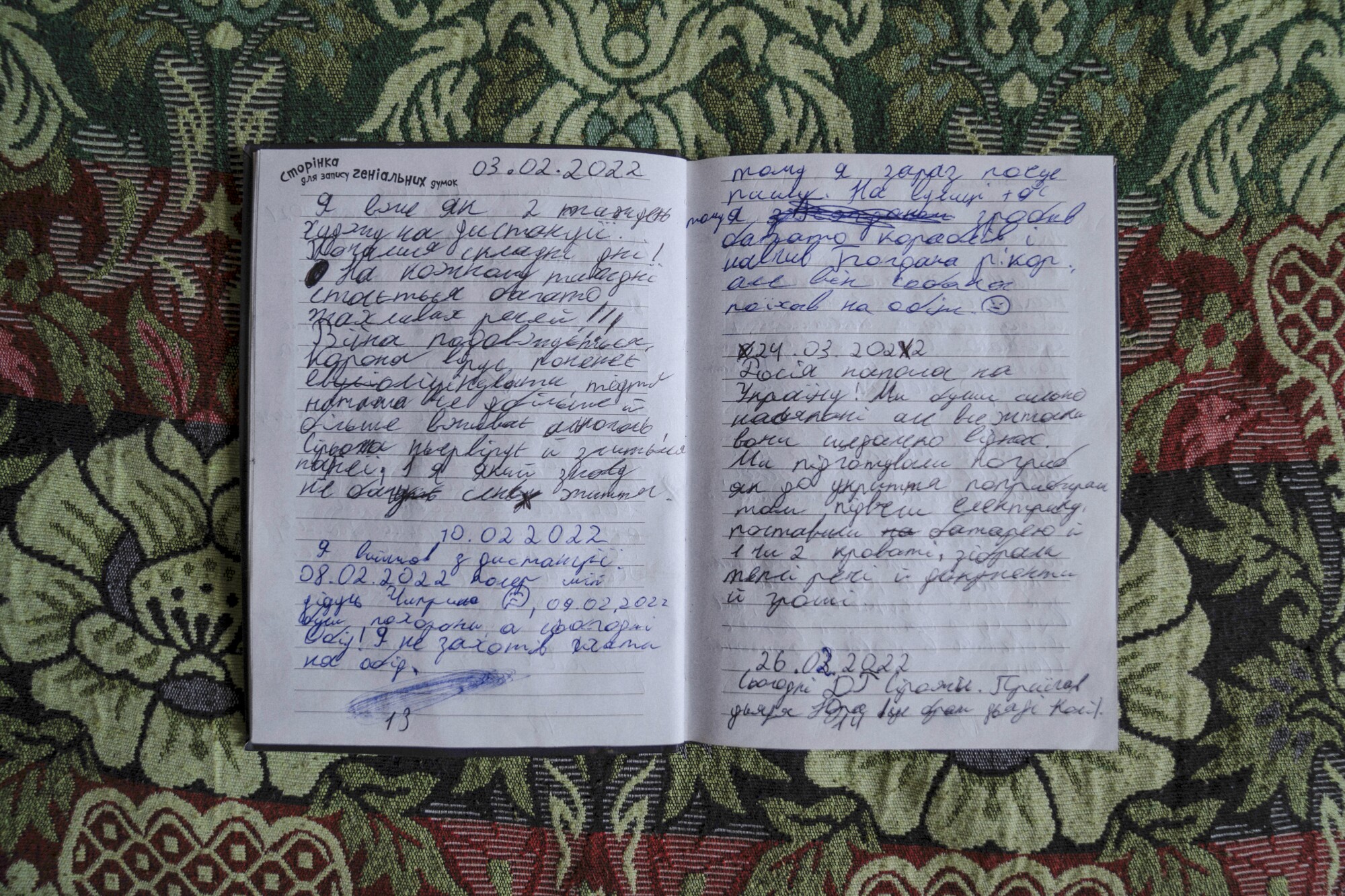

Diary as artifact

Poet and literary scholar Anna Jackson was researching the private papers of novelist Katherine Mansfield for her book "Diary Poetics" when she made an unexpected discovery. Jackson came across a "piece of the world" that was also an element of Mansfield's journal – a kowhai flower between two pages in a notebook:

"After all this time, there it still was, still yellow, still between the same two pages Mansfield had placed it between all those years ago. A piece of the world she wrote about was right there as a piece of the world still, not a piece of writing."

Jackson's experience shows the power of holding in your hand the diary as a physical object. What scholars call the manuscript's "materiality" links writer to reader in an unexpectedly intimate way.

For historians and diary scholars, manuscripts are artifacts. A book's binding, paper quality and ink can signal an anonymous diarist's socioeconomic status. Changes in penmanship may show how the writer felt – drowsy, extra careful or agitated – while writing certain passages.

Some clues, like the bit of evidence provided by inserting a memento, relay intentional messages. Others, like crossed-out words, may reveal information the writer did not plan to share.

Physical evidence can also hint at what happened after a text was written. Damaged or missing pages may indicate a strong reaction to the contents. A few years ago, conservators at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England, discovered a concealed entry in the diary of a 17th-century British sailor. In his diary, he originally confessed to committing a rape, but later wrote a different account of the event, pasting the new page so carefully over the original that it went unnoticed for more than 300 years.

Digital yet material

Every original mark in a diary reflects an impulse of the moment. As diary instructor Tristine Rainer says in "The New Diary," "At any time you can change your point of view, your style, your book, the pen you write with, the direction you write on the pages, the language in which you write, the subjects you include.... It's your book, yours alone."

With so many convenient features, digital diaries remain a popular choice. This option, we might be surprised to learn, even has its own form of materiality.

In "How to Read a Diary," literature scholar Desirée Henderson notes that digital diaries, too, are objects, shaped by tools the diarist selects – in this case, software and hardware – to create the diary. The writer's design choices, such as site structure, networking parameters, embedding of graphics, image and audio files and hyperlinks, offer grist for interpretation not unlike reading the nonverbal signs of a traditional diary.

Woman writing in bed (Getty Images/luza studios)

Writing into the future

As I thought about offering my students the online option, I began to imagine them many years from now, coming upon that London diary from their college days. I remembered my first group of students drawing sketches on their pages, attaching a Travelcard, café napkin, or theatre ticket. I remembered Anna Jackson with the kowhai flower. I couldn't shake my conviction that future diary readers will be less enthralled by a digital product – even enhanced with multimedia – than by the quirky, untidy books hand-lettered by their predecessors.

In the end, I assigned my students – at least those who were physically able – to create their London diaries by hand. They could still use their phones to capture images or take preliminary notes, but in the end they would produce a material keepsake.

Several students decided to write in their notebooks while also keeping a digital diary. The dual process felt natural to them. To his blog Jonathan posted, "Like many children of the 21st century, I love the idea of keeping everything journaled online. This way I can make notes on my phone as I walk, have them automatically update on my computer, where I can expand with more time. If I wake up in the middle of the night with an idea, I don't need to wake up a roommate with a lamp. However, the course also requires an analogue diary."

Every diary, "analogue" or digital, can be read as an artifact layered with meaning – one that conveys clues to its writer's life and times in both non-verbal signals and words.

Paula Vene Smith is a professor of English at Grinnell College who teaches and writes about diaries.