By Tim Holman

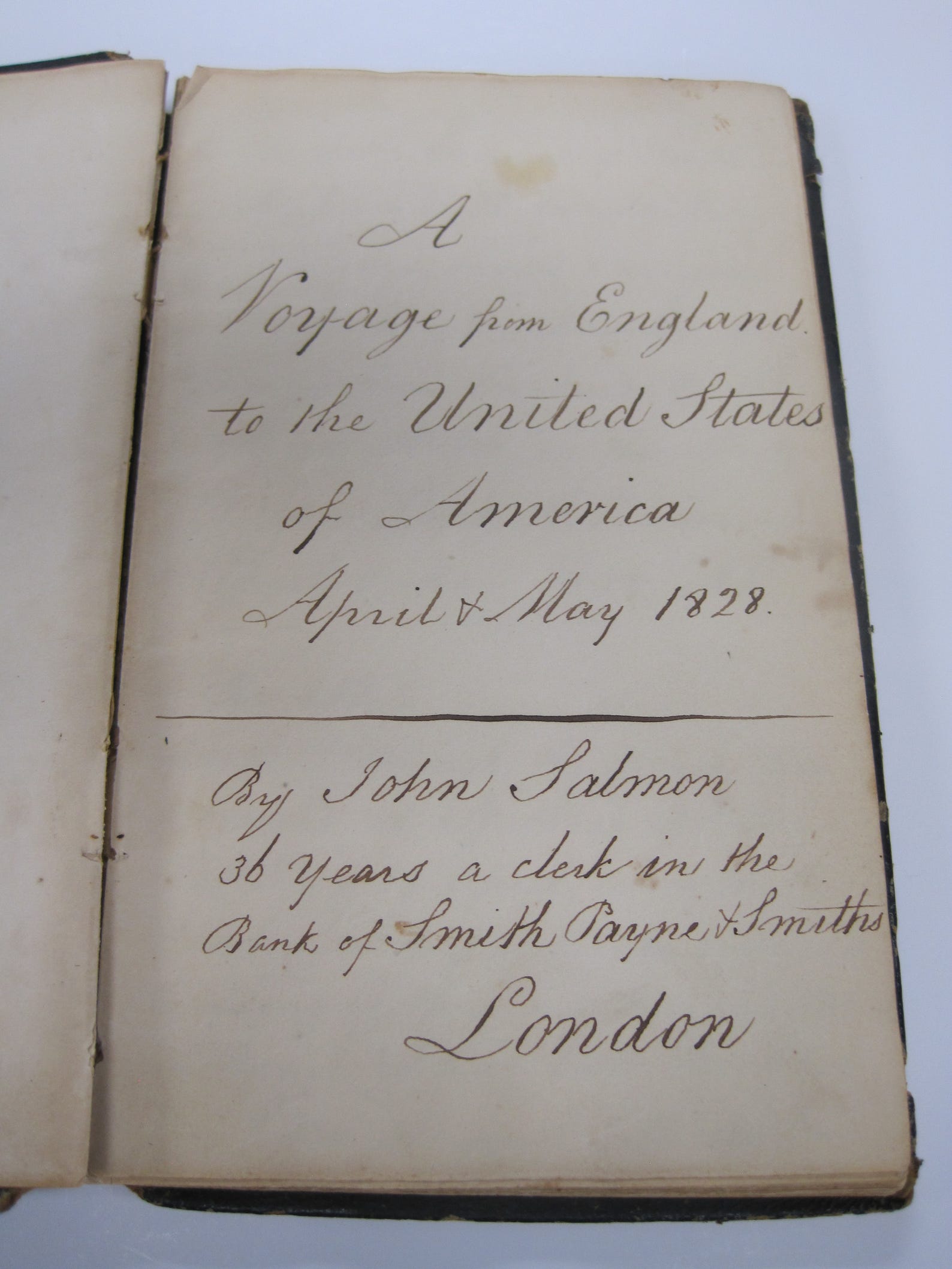

Slow as always, I've just realised that this blog contains no mention of my own book, An Oxford Diary, which was published in 2019. It's unlikely that many people will ever read this, so I'll jot down a few words now.

My book contains an edited sample of the handwritten diaries that I scribbled as an undergraduate at Oxford between 1977 and 1980. There is much to be said for writing something down and then waiting 40 years to publish it. For one thing, after 4 decades there's a lot less work to do - writing, for a starter. More importantly, after that amount of time one's jottings can reasonably be classified as a minor piece of social history since they reflect the values and use the language of the time in question.

I always describe my 3 student years as a "white-knuckle ride", since the ridiculous number of extra-curricular activities that I took part in always threatened to leave insufficient time for studying and getting a degree, which after all was meant to be the whole point of the exercise. The diary is a seemingly endless succession of essay crises, worries about finding accommodation for the following year, money crises in the business world of student journalism, revision crises for imminent exams, and much else. It was all 'go' in those days, or to put it another way I spent the time "doing" rather than "being." I hadn't expected my time at Oxford to be like this, but it was certainly an education in the broadest sense.

Trinity College "Freshers" October 1977

Why publish at all? After 1980 the diaries joined those from previous years and sat on top of various bits of furniture in various lodgings in various locations and did no harm to anybody during the next 25 years or so. And yet, and yet, my time as a student had had a beginning, middle and end, unlike the regrettable shambles that has comprised so much of my life. There was something THERE, a story, even though my diary was more Adrian Mole than Samuel Pepys.

At the beginning of 2006 I had just moved to a new city (yet again), was out of work, and had time on my hands. Meanwhile my Oxford college, Trinity, had established a successful archive and was grateful to receive historical artefacts concerning any events from its distinguished history (it was founded in 1555). I had already contributed a few items (photos, college magazines), since the archive hadn't yet received much from the late 1970s. Would my diary be a worthwhile addition? No! Surely not! My own student lifestyle might horrify the eager, innocent and earnest youngsters who would now be at Oxford. Even worse than that, the original manuscripts would have to be typed out, and that would require application and hard work. Ugh!

On the other hand...

I picked up the 4 original diaries from the bit of furniture they were sitting on, opened the 1977 one and pondered. I decided that it would be possible to start typing and if the content was rubbish I could call the whole thing off and go back to the pub. Having reached this brilliantly logical conclusion, I went back to the pub but remembered to start typing into my laptop computer the following morning.

The project hung in the balance, but as I typed former colleagues and various long-forgotten incidents bubbled up from the dark depths of my sub-conscious mind. "It really was like that!" I exclaimed to my bemused cat, Tigger, who responded calmly. After some sections I added footnotes when I felt that explanations were needed to clarify certain points. To cut a long story short, roughly 2 months later the typing was finished and when printed it covered 200 A4 pages. This was easily enough for a full-length book.

Mind you, I didn't include everything. The original diaries contained long sections about my vacations, snippets of national and international news and weekly Top 10 Singles and Albums charts. I also had a fat file of letters received from relatives, fellow students and tutors. Adding all that stuff would have doubled or tripled the length of the book and made it unreadable (if it wasn't already). There were also - how can I put this? - a few choice epithets scribbled in haste at stressful moments that I decided were a bit too rich for the pudding and were therefore omitted. (If I hadn't done this, the eventual proof reader of the manuscript would have spiked them without hesitation.)

I saved the finished product in 4 separate files on my computer and also had the presence of mind to email them to myself, so that they could retrieved from cyberspace if the hard drive crashed, or something. Job done. But to publish now? It was only - only! - 26 years since I had graduated, and some of the events, essay crises etc were still too embarrassing and fresh in my memory to bring to other people's attention just yet. I went back to the pub and had a think.

The "Cherwell" newspaper's staff, Christmas 1978, yours truly seated in the front row on the right.I then returned to the world of work, and had 5 hugely unsatisfactory years followed by 8 quite good ones. By 2019 I was redundant again but at least had a small ££ payoff to splurge on something worthwhile, or possibly deranged. The 4 files of my Oxford diary were still waiting patiently on my computer, and since 40 years had now passed my embarrassment about their contents had abated slightly. Browsing the back pages of the 'Oldie' magazine, I saw an advert by Janus Publishing, based in Cambridge. "Your book is written to be read," it announced. Well, that sounded like quite a good wheeze after all my years of prevarication, so I made a tentative enquiry, we agreed terms, and the publishing process finally began. Hurrah!

I chose the title An Oxford Diary because it was accurate and suitably modest. But thank goodness I decided to employ a professional publisher, rather than upload the diary's files by myself to a blog or whatever. The proof reader did a superb job raising queries about the text, and emails went back and forth between us. She spotted things that I never would have done. For example, a particular problem was my inconsistent use of apostrophes when applied to proper nouns: was it Browns restaurant, Brown's or Browns'? I had used all 3 spellings at different times and now had to choose one for consistency's sake. She also - how can I put this? - discovered one or two choice epithets that my initial editing had failed to spot, and earnestly requested their removal (which I approved).

This took about 3 months. Then the first draft of the finished book came to me to check. It looked great and very professional, but the page numbers had gone haywire after page 13. So I manually noted down the correct ones, checked these against the page numbers shown in the list of Contents to ensure there weren't any discrepancies, and submitted the changes. (You really have to do this kind of work to experience and appreciate all the fiddly bits involved with publishing something.)

Job done. Nearly there! But now there was the ticklish decision about what to put on the front and back covers of the book. The publisher had drafted a rough design, and gave me the choice of brown or dark blue for the background. I immediately, and decisively, opted for Trinity Blue, and also provided a brief autobiographical note and a suitably tiny mug shot for the back cover.

But what photo should go on the front? My first suggestion was to use a royalty-free pic uploaded from the internet. Maybe a view up the High, or Carfax, or something suitably Oxford-y. But the publisher feared that somebody might claim copyright infringement. No problem, I replied. I'll tootle up to Oxford at the weekend and take a few pics with my trusty digital camera.

So on a beautifully sunny Saturday, 31st August 2019, off I tootled and was in Oxford by 9.30am. My first photo was the obvious and appropriate one of Trinity chapel, as seen from Broad Street. Then I clicked my camera at the Sheldonian and the Radcliffe Camera, strolled up the High, clicked again in the direction of Carfax and Cornmarket Street, had (another) breakfast and then caught the train home to examine the results...

Oh. Hang on a sec. Come to think of it, I caught the train into London and visited a few pubs in Hampstead. Never mind. The NEXT MORNING, at home, I examined the results and decided there was a problem. Namely, even small and cheap digital cameras like mine take photos that are razor sharp with lashings of brightness and contrast. But my diary covered events that had occurred 40 years previously, and a spectacularly colourful photo taken in 2019 might give a misleading impression of the book's contents. Hmmm. Perhaps I had a black & white photo from the late 1970s that could be used instead? A quick flick through old albums produced two possible candidates: Trinity chapel; or a view of Trinity's garden taken in the Spring of 1978 with various people loafing about on the grass. Since my diary was Trinity-based but not about the college per se, I opted for the garden photo as being more Oxford-y, other-worldly, Brideshead Revisited and all that. I sent it to the publisher and that's the one they used. (My sister described the photo as "intriguing" and said I'd made the right choice. Phew!)

Front Cover

A month later, on 1st October, the book was published and (for what it's worth) I was very satisfied with the result. Was it/is it any good? Frankly, I've no idea. It is simply what it claims to be, and despite some obvious flaws it is at the very least an authentic diary. People are entitled to their opinions and can say what they like as far as I'm concerned. I was grateful when the 'Oldie' magazine described it as a 'minor masterpiece', and Chris Gray in the Oxford Times was very complimentary.

That was good enough for me.

Will I publish another diary? No fear! I've written plenty of others, but none of them tell a story like my 3 years at Oxford. In the words of Martin Amis, "Perhaps once is enough - but not more than enough." *

* Amis, M. (1977). Martin Amis. In: Ann Thwaite. (Ed). My Oxford. 2nd ed. London: Robson Books. p.213.