From theconversation.com

By Linda Daley

Picture the scene. It is the closing years of the Austro-Hungarian empire, before the Great War changed such scenes forever. A young man with sound prospects is to meet his fiancée’s father for the first time.

The convention of the day would require him to lay out his credentials and his family’s pedigree for the match to proceed agreeably. But in response to the imagined and real interrogation, both of which generate feelings of guilt and shame about his intentions, the young man instead declares to his prospective father-in-law, by way of a letter: “All I am is literature, and I am not able or willing to be anything else.”

The Diaries – Franz Kafka, translated by Ross Benjamin (Shocken)

Franz Kafka (1884-1924) was nearly 30 years old and engaged to Felice Bauer when he made this exorbitant claim. It was the first of three engagements: twice to Felice and later, quite briefly, to Julie Wohryzek. The decision to put his thoughts in a letter was entirely consistent with the epistolary nature of his relationship with Felice. They saw each other infrequently during their four years together.

Notably, Franz did not declare to Herr Bauer: “I am a lawyer working for a workers’ insurance company, but my real passion is fiction writing.” Nor did he say: “I have a responsible and reasonably well-paying day job, but spend my nights writing stories in my parents’ apartment in Prague where I live.” Missing was the schmoozing of: “Literature is my primary interest – along with your daughter, of course.”

Each of these statements would have been true, although none would have struck the same kind of truth as his actual declaration – to himself as much as to his addressee – that he was, as he wrote in his diary, “nothing but literature”.

The letter to Herr Bauer never arrived. Felice intercepted it.

Uncanny writing

What Kafka expresses in the letter is a commitment to something other than a life to be lived and shared with Felice, something other than what today would be called a lifestyle. As his dairies repeatedly show, Kafka’s life, his existence, was literature, and that existence was not shareable as a “lived experience”.

He was often in pain, fatigued, or simply distressed by his body’s puniness. He despaired of the obligations of family life, the noisiness and nosiness of his parents and siblings. He was deeply conflicted by the necessity to undertake the paid work that sapped his energy. Each of these things he saw as challenges, counter forces, to his writing.

Yet this hardworking, clever, funny and eventually chronically ill young man was not a hermit. He had friends, admirers, colleagues and lovers aplenty.

Kafka’s sensibility was aslant to the conventions of bourgeois life, but it chimed with a certain European modernity that was, around that time, expressing its disenchantment with the world. His existence was entirely directed towards what was, for him, both the necessary and the uncanny nature of writing.

For Kafka, writing was a strange way of thinking and being in the world. It was a force to which he could only submit, an existence that joined up with and tore away from his own. It was so much more than a mode of expression. It was more than an activity undertaken to build the kind of literary legacy that his friend and fellow writer Max Brod (1884-1968) desired for him.

Felice and her father each recognised this paradoxical relation to life in Kafka. In his diaries, describing the “tribunal” where his engagement to Felice was broken for the first time, Kafka noted: “Her father grasps it correctly from all sides.”

Franz Kafka, 1923

Kafka’s literary legacy

In 1917, Kafka was diagnosed with the tuberculosis that would eventually kill him just before his 41st birthday. The small number of stories he published during his lifetime amounted to no more than 300 or so pages. The most well-known are The Judgement (1913), The Stoker (1913), The Metamorphosis (1915) and In the Penal Colony (1919).

Brod became Kafka’s literary executor. He managed the posthumous publication of his friend’s three incomplete novels The Trial (1925), The Castle (1926) and The Man Who Disappeared (1927) – also known by the title Amerika. He also took possession of the 12 notebooks that constitute Kafka’s “diaries”, bundles of papers, and some letters.

Kafka’s instructions were to burn the lot. Brod’s refusal has long been the subject of speculation.

Perhaps more than those of any other published writer, the diaries of Franz Kafka have a special value in providing insight into his modest but profound literary output. Ross Benjamin’s new translation of Kafka’s dairies makes available the German critical edition published in 1990, which corrected the elisions, amendments and misrepresentations in the edition Brod published as two volumes in 1948 and 1949.

What a joy it is to read Kafka disentangled from Brod’s oversight. But why was he entangled in the first place? Kafka was hardly a household name during the mere 15 years he was publishing, beginning with The Aeroplanes at Brescia, which appeared in the Prague newspaper Bohemia in 1909. It was another four years before his short fiction began to appear in print.

Kafka was aware of the limited interest in his writing beyond a small group of loyal supporters, at the centre of which was Brod. This was confirmed in an embarrassing episode when the well-known Czech writer Carl Sternheim, with whom Kafka shared a publisher, was awarded a literary prize, but directed his publisher to hand the prize money over to Kafka on the presumption that Kafka was impoverished.

Kafka initially refused the money because he felt it was being bestowed by someone unfamiliar with his work to avoid the bad optics of the prize going to an already wealthy author during wartime. Publicly, he said he was not as poor as the poorest eligible writer. Privately, he called it an act of misplaced charity, although he did eventually accept the money. Without any immediate need of it, he invested it in war bonds. It was the only literary honour Kafka would receive during his lifetime.

Kafka’s publisher Kurt Wolff was a keen supporter of his writing. But when war broke out in 1914 – just as Kafka’s writing was hitting its straps – Wolff enlisted.

The publisher to whom Wolff handed the management of his business, Georg Heinrich Meyer, was also enthusiastic about Kafka’s writing. But according to Kafka’s biographer Reiner Stach, Meyer was probably quite ignorant of its real worth. Meyer had a background in the business side of publishing; he showed little interest in cultivating relationships with authors or discussing the literary content of their work.

It thus fell to Brod to establish Kafka’s posthumous legacy as a literary genius. He ensured that few would now question Kafka’s place in the pantheon of modernist writers. But in doing so he tightly entwined his own literary reputation with that of his friend.

He did this in his own writing, first in a fictionalised account of their friendship, The Kingdom of Love (1928), in which Kafka is figured by the character Richard and Brod by the character Christof. Brod also wrote an “objective” biography of Kafka (1937), in which he states:

I lived still with my unforgettable friend […] I asked him questions and could answer myself in his name.

Brod’s writings about their friendship established a mythologised Kafka, who lived on, fictionally and biographically, through Brod’s name. His influence over Kafka’s estate was not simply one of editorially securing the works’ publication. In a short story collection, Brod included an appendix guiding readers on how to interpret the stories, believing only he held the key to unlocking the meaning of the genius’s work.

A forge for sentences

Ross Benjamin acknowledges that Brod’s relationship with Kafka was valuable in securing an international reputation, beyond the small and enthusiastic readership he had while he was alive. But this also meant Kafka’s reception was influenced too heavily by Brod’s concern with his own reputation.

Benjamin’s new translation of Kafka’s diaries, in their presentation and arrangement, enables English readers to see them, for the first time, as the forge of his craft. It builds on the German critical edition, as well as decades of work by many scholars. We can now read in the diaries Kafka the writer rather than Kafka the author.

Restored is the sentence craft as it was being forged, smithy-like, across the 12 quarto and octavo notebooks that Kafka called his Tagebücher (diaries), written between 1909 and 1923. Restored are the frequently ungrammatical and sometimes half-legible sentences that Brod often completed or replaced with the syntax of High German. Restored are the homoerotic observations, descriptions of visits to brothels, and negative comments about well-known people, including the odd barb directed at Brod himself.

Most pleasurably, the new translation restores our sense of proximity to the pen and ink. It allows us to experience the falling off and starting again of sentences, the sometimes awkwardly expressed passages, the unreadable words due to ripped notebook pages, and the arresting effect of marooned and perfectly complete passages that are reforged across several pages.

Consider the following being hammered and shaped in the early drafting of the story Description of a Struggle:

You I said and gave him a little push with my knee (with this sudden burst of speech some saliva flew out of my mouth as a bad omen) don’t fall asleep.

The same sentence is repeated, word for word, many entries later. But on that same notebook page quotation marks are toyed with and a sentence is added:

“You” I said and gave him a little push with my knee (with this sudden burst of speech some saliva flew out of my mouth as a bad omen). I haven’t forgotten about you he said and shook his head even while opening his eyes.

In an entry that begins “He seduced a girl in a small town in Isergebirge”, we learn from the critical note attached to it – one of 1,400 meticulously detailed notes – that the passage is likely crafted from direct observation during one of Kafka’s work travels, and that it possibly builds upon an actual liaison he had with a young woman (referred to as G or W, the notes tell us) during those same travels. A little later, we read:

Nothing, nothing. In this way I make ghosts for myself. I was involved, even if only slightly, solely in the passage […] For a moment I thought I saw something real in the description of the landscape.

What matters more than the status of the seduction passage – whether it is a sliver of fiction or a sliver of Kafka’s life – is the feeling we have of being just behind Kafka’s shoulder watching him re-read and re-evaluate what he has written.

The diaries include writing in a variety of genres: descriptions of theatrical performances, recollections of dreams, fiction tryouts, reviews, observations of other people, annotations of other writers’ work, essays on various topics. Combined with the lack of signposting, the effect is that the writer’s “I” is disaggregated and distanced from the writing. Notice the displacement in this entry, for example:

A person who has no diary is in a false position in the face of a diary. When, for example, he reads in Goethe’s diary that on 11 January 1797 the latter was busy at home all day with various arrangements, it seems to this person that he himself has never done so little.

It is often unclear in the notebooks whether the “I” or the “he” that announces itself on the page is Kafka, or one of his characters, or someone he is ventriloquising. The dairies require us to suspend our familiar habit of asking who is speaking and trying to place who is being referred to. Instead, it becomes necessary to focus on the image the passage brings alive.

The law of the diary

It is striking to hold the two editions of Kafka’s diaries alongside each other to see how the new translation, in reclaiming the liveliness of the writing, also produces the occasional discombobulation that results from his writing practices.

Kafka frequently returned to old notebooks to make entries after new ones had been started. This criss-crossing is reproduced in the new edition, which is organised by notebook, not by year as in the Brod edition.

Reading naturally goes forward. This parallels the way we habitually think of the movement of a life and its recording in a journal. With the criss-crossing of entries across the notebooks, however, the reader’s attention needs to be sharp. Where a life or a book might move in a one-way direction, the craft of writing does not. Kafka’s notebooks reflect the flux of writing, faithfully restored in the new translation.

Maurice Blanchot tells us the only “formidable law” of the diary is that it must respect the calendar. To note the date, Blanchot says, is to record the passing of time and provide the illusion that the writer lives twice: once by warding off forgetfulness and the despair of having nothing to write; twice by noting that they are writing in their diary about having nothing to write.

Frequently, Kafka abides by this law:

Wrote nothing […] Wrote almost nothing […] Awful. Wrote nothing today. No time tomorrow.

Within a few weeks, however:

This story “The Judgment” I wrote at one stretch.

And later still:

It has become very necessary to keep a diary again.

As the notebooks start increasing, the dating falls away, transgressing Blanchot’s law completely.

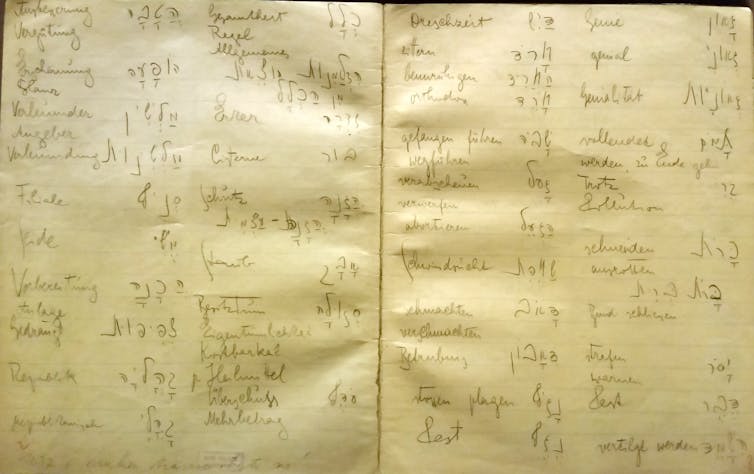

Pages from one of Kafka’s notebooks with words in German and Hebrew. National Library at Givat Ram, Jerusalem/Wikimedia Commons

Pages from one of Kafka’s notebooks with words in German and Hebrew. National Library at Givat Ram, Jerusalem/Wikimedia Commons

A new literature

Kafka’s occasional reflections on his diary-keeping are less about the personal insights, or what might be called the conscience, of the writer. They are not defined by their confessional sincerity. Rather, they enable him to self-display. The diary entries provide him with a visualisation of the movement of his thoughts and their alignment on the page.

The diaries act not only as a forge for Kafka’s writing; they also forge a new possibility for the diary’s place within literature. In several entries, Kafka comments on his intention to start an autobiography, implying he did not see the writing he was doing in the notebooks as having an autobiographical purpose.

He also makes the allusive suggestion that diary-writing has its analogue in the literature being produced by his Jewish contemporaries in Warsaw and Prague.

This new literature, Kafka says, is united by a Hebrew mother tongue assimilated within the dominant German language culture. It was a literature seeking modes of expression for the effects of that assimilation. Kafka viewed the experimental writing of his peers as a form of literature that can be viewed as the

diary keeping of a nation, which is something completely different from historiography […] the detailed spiritualization of the extensive public life, the binding of dissatisfied elements.

Diary writing can be seen as a means of self-formation, not only for an individual, but also for a “small nation” of a marginalised language culture. It offers new and uncertain modes of expression. Kafka adds:

literature is less an affair of literary history than an affair of the people […] everyone must always be prepared to know, to defend the part of literature that falls to him and at least to defend it even if he doesn’t know or bear it.

Decades later, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari would mine this entry in Kafka’s diary to coin their idea of “minor literature”. They argued that major or dominant languages, such as German and English, not only produce the spoken dialects of the minority cultures they incorporate or colonise; they also enable new modes of literary expression by writers from minor cultures writing within those major languages.

Kafka spoke High German; his writing bore little or no trace of Prague-German. But this diary entry opens up the possibility of a new way of conceptualising the politics and poetics of literary expression. Such an understanding is now central to literary criticism in colonial and postcolonial contexts.

Blanchot tells us there is no law without its transgression. The new version of Kafka’s strange and extraordinary diaries reminds us how diaries are not usually intended for any reader other than their writer, who is usually their only reader. Ross’s translation will continue to ensure the transgression of that law too.

It is just shy of a century since Kafka’s death. What could be more fitting than the appearance of these diaries in a faithful translation, showing them to be much more than an accompaniment to Kafka’s stories or a calendar of his existence? They are an inexhaustible source of literature itself.

https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-all-i-am-is-literature-franz-kafkas-diaries-were-the-forge-of-his-writing-196573

.jpg)