From theguardian.com

By Anna Tims

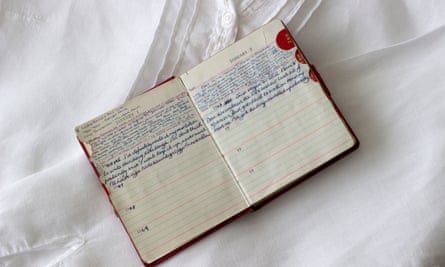

"Hello! I said to myself today that if I do five handstands and flip over it will be an excellent year and I did!” Thus, unceremoniously, began the 41-volume (and counting) story of my life. It was 1984 and I was 14, fumbling through adolescence in a scarlet beret. My likes, according to a list on the front page, included jacket potatoes and graveyards. My new year resolutions were to “see how long I can go without cake” and “improve my character.”

I haven’t missed a day’s entry since that 1 January. My past crams two bookshelves in rows of page-a-day journals. It’s startling how little four decades seems when it’s represented by slim, stacked spines.

I have little idea of the tales they tell. Most of the entries have lain unread since I wrote them. Yet every morning, I hunt down my fountain pen (life must be recorded in a pen that takes itself seriously!) and write up the previous day. If ever I were to miss one, it would seem it had never happened; if my diaries were lost, I’d feel my foundations had buckled. Journaling is a chore and a panacea, and yet I still can’t fathom why I do it.

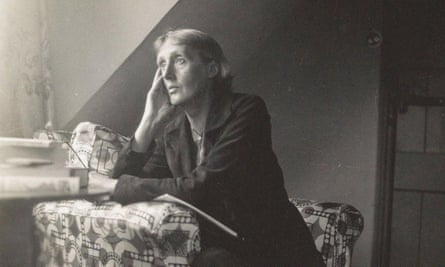

There are many reasons, according to Fiona Courage, director of the Mass Observation Archive that collects personal records of everyday life in the UK. “Some people want to leave something of themselves to posterity,” she says. “Some find it therapeutic. Virginia Woolf’s diaries were a way of practising her writing.” Courage says that the habit soared during the Covid lockdowns as people realised that they were living through history. “Diaries give you the ability to distil your experiences and make sense of them,” she says. “For historians they are priceless as they record social trends, layers and details that wouldn’t make it into the history books. They plug a gap in the everyday.”

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) wrote diaries to practise her writing. Photograph: Alamy

I had no inkling of what I’d started when I recorded that first New Year’s Day. My mother, a local historian, had nagged me for years to keep a diary so that future generations might learn what a 20th-century teen did for fun and ate for dinner. It was more an urge to write that motivated me to begin. I did not, I had sadly discovered, have a novel in me. There was a point, I like to think, when it dawned on me that life is its own story. A series of chapters, an evolving cast of characters, a thickening plot and an unguessed ending.

Those future generations will have a very misleading idea of the 20th-century teen. Doris Day provided the soundtrack of my youth. My recreation was climbing trees. While classmates danced at discos, I was in bed with Anne of Green Gables. Adolescent passion passed me by entirely. My heart was broken by the deaths of pre-war film stars, announced in lurid felt tip in the page margins, rather than boys.

Over the years, the entries evolved from a record of school lessons and domestic routines to confessional and reportage. And I can chart my startled ageing: “I’m much too young to be so old so soon,” I marvelled on my 21st birthday.

On my 30th: “My face is lumpen, my body stale and my hair like tinned sardines. Feel every inch of 30.”

When 40 arrived: “My haemorrhoids are growing and my brain is shrinking. However, I am quite contented to be 40, if a little awed by my antiquity. I have always known that middle age would suit me and feel qualified now to march about in large hats berating miscreants.”

Fiona Courage, director of the Mass Observation Archive, says: ‘Diaries give you the ability to distil your experiences and make sense of them’. Photograph: Roger Holfert/Alamy

Now, when I look back on them, those volumes do read like a story. A chronicled life seems more like a plot with a sense of direction than a puzzle of random events. The darkest times – the night my mother was run over and the long years of her recovery; two unexpected redundancies – are, reading back, no longer isolated intrusions, but part of a developing narrative. I can read the chapters with a God-like omniscience. I’ll know, if I follow that misfit teenager through four years of school, how things turned out. Which hopes came good, which friendships lasted; how, now and then, foes became benefactors.

I could trace how becoming a university sacristan at 20 to please a dishy chaplain began a chain of events that led, seven years later, to my husband. Or, further back, how a crush on my new German teacher at 14 inspired me to study German at university where I encountered that dishy chaplain. I know that the self that celebrated the arrival of 1996 as a sorry singleton (“While the others waltzed, J and I washed up and reflected mournfully on our unloved state. It’s a condition that has landed us the worst bedroom behind the wellington boot depot. No one brings us tea in bed and no one dances to the Pogues with us”) would meet at a ceilidh, before the year was out, the man I was to marry: “I found myself paired with a priest. I was instructed to ‘grab his left’ and do a Doozy Doo. He kept coming back for more, so we ‘stripped the willow’ successfully together and later I found myself contemplating the pros and cons of marriage to a curate.” And I can confirm that five handstands and a flip ensured that 1984 was “not at all bad, despite Orwell’s ominous predictions.”

You pay more attention to the world when you know you’ll be writing it up. I pen character sketches of strangers I meet – a pony-tailed sheet metalworker from Avonmouth who revered Prokofiev, the substantial matron in a waiting room “who described to me her knicker situation”. I want to do justice even to the dullest day because life is a privilege and the mundane of today will be tomorrow’s history.

I recorded my first sight of a mobile phone, wielded from a pulpit as a spiritual aid, in 1985: “‘Can anyone tell me what this is?’ asked Father R, holding up what looked like a bendy grey banana.” In July 1996, I sent my first email “all on my own”: “This,” I marvelled, “could become an addictive device. [My colleague] and I spent the morning pinging simpering messages to each other across the desk like toddlers with toy phones, but they take up to an hour to arrive so I shall still prefer faxes.”

Dear Diary… Anna Tims with her life’s work at her desk. Photograph: Alun Callender/The ObserverIn the privacy of a diary, ego can take precedence over world events. Wars raged, governments came and went while I focused on domestic headlines. “Today, I threw out the old Boden catalogue,” began 20 January 2009. “Barack Obama was inaugurated president also, so one had a vague sense of historic-ness as one flossed and hoovered, but the former event seemed to me more significant!”

It’s never too late to start a journal and a life is never too dull to record. As the years pass and memory fades, I find it a comfort to know that I can dip at will into childhood or child-rearing and that milestones are preserved. I imagine my future self in a care home, faculties slipping, reliving my first property purchase: “I examined my feelings at being a flat owner, but it didn’t seem real. I must buy some hyacinths and cats.”

My first date: “I wish I hadn’t said my beer tasted of pus; he must now think I suck boils!”

My first born: “All of a sudden E was holding a large, pink, alert baby of a size quite unfeasible given the manner of exit. It didn’t seem remotely real that this was mine.”

I feel that if I were to read from the first entry to the last, I might find an answer to a question I can’t articulate. But time travel can become unhealthily consuming so I do it sparingly. The past still lives on in those pages and I can feel it closing over me if I linger there.

In lockdown, I read every day of my university years. It was like reading a novel about someone else. I read in suspense of predicaments I no longer recalled and of dramas whose endings I’d forgotten. Unremembered griefs were disinterred; dormant grievances rekindled. Long-lost friends jived to Abba in my student room and long-dead voices spoke again. When I closed the volumes, I emerged blinking into a different century, a different home and a different family and marvelled at the chain of successive days that had brought me here.

But some things are constant. It’s simultaneously reassuring and dispiriting that I remain recognisably the same me from 40 years ago. I continue to transcribe my likes at the front of each diary and jacket potatoes and graveyards reliably top the list. I remain faithful to Doris Day and still wear a red beret.

It’s a weighty business recording a life, yet it’s taught me not to take myself too seriously. When painful moments are written down I can more easily let them go. Seeing life as a story with an unknown number of chapters left to write is both exciting and daunting. My children are already alarmed at the space my life will take up on their shelves when it’s over, but I plan to chronicle the days until I can no longer hold a pen. The only part of the story I’ll never get to write is the ending.