From rte.ie

By Amy Prendergast, TCD

Analysis: The diaries tell us much about the women's lives, their creativity and their contributions to culture

Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, 'The Ladies of Llangollen' c.1830–1856. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Diaries written by women in 18th century Ireland are still to be found in libraries and archives throughout Ireland, the UK, and Europe. They were usually deposited as part of a family's papers, and have tended to remain untouched and unloved for decades. Whether motivated by a creative impulse or an important life event, Protestant women of all ages took to keeping a diary in 18th century Ireland, experimenting with writing styles and recording a curated version of the world they found around them. What can we learn from these diaries about women's lives, their creativity, and their contributions to culture?

Diaries weren't always the work of just one person

We can see instances where the handwriting changes in the diaries. For example, the diary of the young Letitia Galloway is continued by her mother when she is away for a few days in Co. Wicklow. Taking up the pen again, she jokingly states, 'I resume my journal which I find my mother has made good use of during my absence’, alerting us to communal writing practises across generations of women.

Women often wanted their diaries to be read

Many of the diaries that survive were intended for a much wider audience than we might think, and most weren't really private at all. Diary after diary speaks to a current or future audience, addressing unknown potential readers. Elizabeth Edgeworth, the sister of bestselling author Maria, used her diary to contribute to her family legacy and record her view of the 1798 Rebellion. She even provided a glossary of terms for future readers.

Elizabeth Clibborn, a Quaker woman who would go on to have at least 15 children, considered the possibility of her diary being read in future by her own daughters, hoping it might provide them with support and advice if they themselves had children. 'Perhaps my dear girls may in perusing these lines receive some information in rearing their dear offspring if entrusted with any'.

Several of the diarists wrote openly about friendships and grievances, before recalling the likelihood that others could read their words and interpret them in certain ways. Mary Mathew from Co. Tipperary, for instance, wanted to set the record straight about her companion for future readers – 'don't let them imagine from this & some other things I have wrote that we don’t live in the greatest harmony together.’

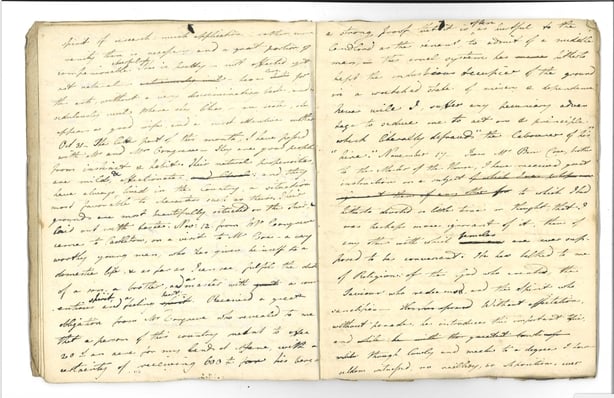

Title page for Mary Shackleton Leadbeater 1772 diary. Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland (NLI MS 9295)Many women used their diaries as a way to manage their mental health

We find multiple instances in the diaries of writers describing themselves as feeling 'pressed down' and suffering from melancholia. Several of the women explicitly used the diaries to try to cope with their emotions and to reduce stress. Anne Jocelyn's diary opens with the explanation that the diary entries were written to 'help to keep off fruitless and unavailing thoughts and give a better employment to my mind'.

Diaries also provided a platform for processing grief. Many were written in response to a diarist’s experience of loss and bereavement, including Jocelyn’s, which began after the death of her husband of over four decades, as well as the short diary of Theodosia Tighe Blachford. The diaries also chart women's experiences of pregnancy, pregnancy loss and infertility, with several also including heartbreaking entries recording the loss of beloved children and babies, such as those written by Melesina Chenevix St George Trench.

Diaries provided testimony when other platforms were unavailable to women

We often encounter the diarists attempting to articulate their experiences of what we'd now describe as harassment and non-consensual touch. We find young women being pulled on to young men’s laps against their will in the diary of Co. Kildare’s Mary Shackleton (later Leadbeater), and others being plied with alcohol, as in the writings of Marianne ffolliott in Co. Sligo.

The diaries gave women a space to set down their own experiences and to give voice to those of others. The diary of Dorothea Herbert records her version of the abuse suffered by her sister Sophia Herbert Mandeville at the hands of Sophia’s husband, drawing on the language of amatory fiction and Gothic novels to convey the horrors of the situation.

Elsewhere, Elinor Goddard's entries employ euphemism in noting William Fownes's pursuit of Sarah Ponsonby (Fownes was her guardian), before Sarah ran away with Eleanor Butler of Co. Kilkenny, the woman who would become her life partner. Butler's own diaries, kept over many years, record the women's lives spent living together in Llangollen in Wales.

Diarists don't always tell the truth

We need to remember that diarists don’t necessarily provide a true reflection of the world around them. The period’s diarists, being largely drawn from women of significant wealth and means, recorded a certain version of the world they lived in. In an Irish context, we can note the absence of references to rural disaffection or unrest, as well as frequent silence on the widespread poverty that existed.

Such descriptions are instead present in the diaries of those women who visited Ireland from abroad, such as Margaret Boyle Harvey and Elizabeth Quincy Guild coming from America, which are filled with reference to poverty and mud cabins. The environments created instead give us an insight into the diarists' vision of their worlds and their perspectives and opinions. They often display great flair in composing their entries, playing with language and frequently emulating the novels they were reading. Rather than considering them exclusively as historical sources, we can approach these diaries as literary works which gave women a space to showcase their own creativity.

Dr Amy Prendergast is the author of Mere Bagatelles: Women's Diaries from Ireland, 1760–1810 (Liverpool University Press)