From voxeurop.eu

A group of students from Lviv, a major city in western Ukraine, are keeping a collective diary for Voxeurop. As far as the situation allows, they write about the Russian army's attack and its impact on their daily lives

25 March

My generation

Kateryna Panasyuk

What will happen after the war? Ukrainians don’t ask this question. We ask: what will happen after we win? It makes such a little difference verbally yet such an important message stands behind these words. Ukrainians don’t give up or give in, cowardice is not an option here. Oh I do get a rush when I say this, you know. It’s true.

Personally I would say there aren’t more than one or two things I love more than my homeland; this land, even this soil itself, is truly the dearest to me. A colleague of mine, Alex from Kharkiv, recently said “What will I say when my children, nephews, grandchildren ask about the war and my participation in it? Will I say that it was interesting, but somehow it passed by me because I spent most of it listening to lectures via Zoom and working on deadlines? Seriously?!”, it was a thought of his in the context of our conversation about studying during war.

It surprised me, I never thought everyone has these thoughts, but it turns out they do. I prefer to keep learning, but the thought of children… Every time I feel like giving up, I remember my generation must be the last one to suffer from Russian imperialism. Our children will not, their children won’t either. They will live on this land freely and they will love it so very deeply.

24 March

Daria’s grandpa and the news

Hanna Shypilova

Daria is 19 years old. In 2014 she and her parents were forced to leave their home city, Luhansk, because of the Russian invasion. Now they live in Kyiv, whereas her grandparents moved to Russia. This particular day has separated them not only territorially but also mentally and politically.

On 24 February the war came into Daria’s life for the second time. Her grandpa called them in the morning, wondering how they were.

“Later, we heard a loud explosion next to us. There were already some videos of it on the Internet and at that time Kharkiv was already being heavily bombed. We sent the video and photo to my grandfather, to which he replied that it was all fake. He spoke with all those phrases that are imposed on Russian television: our President Zelenskyy is a drug addict, we are bombing ourselves. All the rest is nonsense for him.”

Daria’s grandpa always supported Russia. He even tried to pursue her to study in Rostov, because life with “Ukrainian neo-Nazis” is unacceptable to him.

“He does not miss a single news release, and there are morning, afternoon and evening ones. We have not been able to convey the truth and reality to him since 2014, and now everything has only gotten worse. I don’t want to put up with this, but he became a real victim of propaganda. I still respect and love my grandparents, because they are my family. But while he is watching Russian propaganda, he supports everything that is happening now in my country, where children, women and other civilians are being killed.”

23 March

A Story from Mariupol

Hanna Shypilova

“There was no access to drinking water in the city for more than a week, so we started going to the river to collect water. One day when we went to the river and the shelling began. We were lucky, but a shell killed three people who were higher up the hill. On the way back home, we saw many people covered with sheets. They were killed by shells”.

That is the story of a 30 year-old Julia, published by Hromadske. Julia has lived in Mariupol all her life. On 24 February, when Russia launched a full-scale war, the first shells were dropped on her city. Since 2 March, the local people's task was to survive without connection and access to water, gas, and electricity. Only on the 20th day of the war, an opportunity to leave Mariupol appeared.

“I went with my boyfriend and his sister. We cooperated with several other young couples with children. We heard that the road is dangerous, part of it is mined, but it could be seen. There was no thought about whether it was scary to go or not: every day we went to bed and did not know if we would wake up. When you know that there are people who have left, you have hope.”

Now Julia is in Zaporizhzhya, but more than 300,000 people in Mariupol still need food, water, and medicine, while the Russian army is blocking access to humanitarian aid.

21 March

Bohdan, volunteering on the Ukraine-Polish border

Khrystyna Dmytryshyn

“When Russia started a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I dedicated my time to helping Ukrainian refugees at the Krakovets checkpoint. There, more than 2,000 people cross the border daily. The hardest work is when it is cold outside. You have to inform all the people with small children in line that they can go to the tent where it is warm, they can drink tea and eat well”, Bohdan, a young Ukrainian volunteer, told me.

“As volunteers, we always carry small children in our arms to help the parents. Those scared kids are shaking because they are freezing. At night, we put them to sleep with their parents at our volunteer base, where they may warm up. We also give refugees clothes and help to find a doctor. There are many Polish doctors whom we help with translation”, Bohdan added.

“I remember very well one man leaving the country with his two little daughters. It was cold outside, but he did not want to enter our warm tent. However, he agreed later on. He talked quietly and kept a stone face. The man was running away from Kharkiv because the Russian army had destroyed the apartment where he lived. His wife died of cancer a few years ago, and he had to prove this fact with a document to be able to cross the border. I think he was ashamed to leave, but he had to; he is the only parent to his daughters. I think he will come back when we win.”

20 March

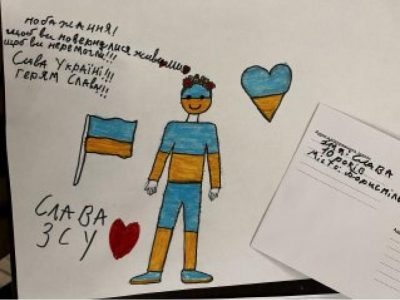

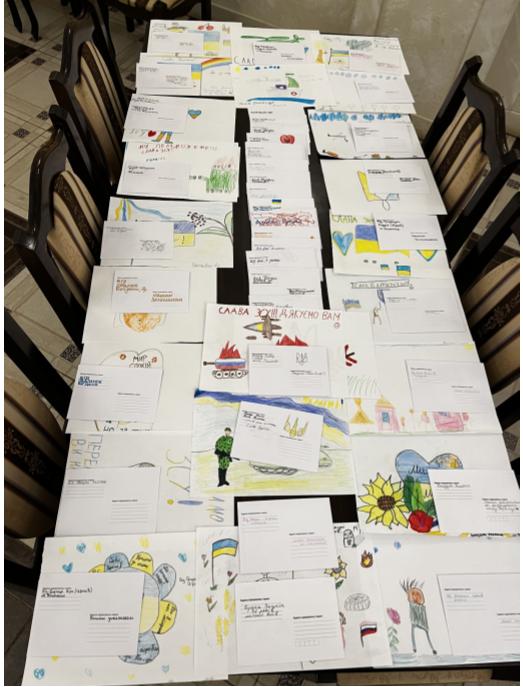

Children of war

Marta Belia

From time to time, the local volunteer centre, where I go to help, organises activities for children. Usually, participants are children from our city, but there were many displaced children this time. Children who were forced to leave everything because of the Russian aggression. They are the same children, they are just as enthusiastic about drawing and running, but you can see that the eyes of these kids have already seen the war and felt its consequences.

The war affected them personally. They are very cheerful and talkative, but there is a sense of adulthood in their words. These children calmly and thoughtfully speak about relatives: fathers, grannies, siblings – who remained in the hot spots, who refused to leave.

They describe how they heard the explosions and how they left their cities. I could barely hold back the tears as I listened to them, but they continued the story calmly. They are still so small, but a lot has happened to them, and they endured it bravely.

I have to admit, I cry and stress because of less horrible things: the air alarm in the middle of the night, horrible news I read; but these children are calm and balanced, although they have suffered much more.

That's why these children impressed me. I'm sorry that the war forced them to grow up too soon, but I'm stunned by their resilience. And I really want everyone who took their childhood away from them to be punished.

18 March

Studying in times of war

Kateryna Panasyuk

It’s incredibly difficult to study now, but I’m happy to do it. It happens that my family and I are blessed with relatively quiet skies and the warmth of our own home – for now. Every night my city, Lviv, wakes up to the sound of sirens. Every night I get yanked out of the warmth of my bed by a horrible rush of adrenalin, change clothes, put on the warmest socks, grab my backpack and run down 8 floors to spend up to 4 hours in a cold bomb shelter. Regardless of all this, my mind is still thirsty for knowledge. It’s always been, but now it’s fuelled with anger. There is no way I will let Russia stop me from reading and learning. There is no way I will let anyone make me useless or less intelligent. I’m not too strong physically, I can’t shoot well and I’m no doctor. But when the time comes, I want every Russian to pay the price for what they did and every Ukrainian to live in a country they deserve. Who else will do it if we stop learning now?

Olexandra Besarab

I understand very well why my university is resuming studies, it is really necessary

But personally, my story – I can not do it. I can't study, not at all. I feel like I'm wasting my time just because the information doesn’t reach my brain, because my head is full of other things.

Nikita Vorobiov

The format which is now practiced in my university works well for me. All lectures are being recorded, so I can always watch a recording when it’s convenient. For example, a student can work during the day and study in the evening. There is also a big relief regarding the deadlines: some assignments were postponed or taken down completely. There is not too much pressure on students now. I live abroad now, no running down to the bomb shelter for me now. But we will see how it goes next week when I come back to Ukraine. For now I think we simply cannot afford to stop studying in these circumstances.

Roman Rozhankivskyi

I feel this bottomless fatigue. My mind finds comfort in involuntary deafness. I hear sounds, but I don't catch their essence. It's as if I'm falling asleep to the voice of the lecturer. And the noise of the Zoom call drives me crazy. I don't have the strength to think about homework or the curriculum. It is difficult for me to develop now. Sometimes I ignore people because of oversaturation with stimuli. And sometimes I experience a phantom air alarm. It feels like it's about to begin. I hear high-frequency sounds and it becomes so scary.

16 March

Nikol, seeking for help in Mykolaiv

Khrystyna Dmytryshyn

Today, I'd like to share this excerpt I translated from a story I've read on Hromadske, an independent news outlet. It was written by Ksiusha Savoskina, and I believe it tells a lot about the situation in Mykolaiv:

“Hi, my name is Nikol, and I need some warm clothing,” said a girl coming to our volunteer centre in a small town in the west of Ukraine. We started opening boxes for her, showing all kinds of sweaters and coats, but she ignored that. Nikol picked a blanket for herself and one for her 2-year-old sibling. “Can you imagine that a small part of a ballistic missile fell right by my high-rise in Kyiv?”, she said with fear and excitement at the same time.

After we hardly gave Nikol two packages of warm clothes, her mom came to the room. When we brought her hair care box, the woman’s hands started shaking terribly, and she cried. “I did not wash my hair for almost two weeks. I cannot even remember what shampoo I used to buy. I am afraid to take a bath and leave my children alone. I hear bombing constantly in my ears. Did you hear it tonight?”

It was the second day the family was spending in Mykolaiv, a small town in the Lviv region. That night, the Russian missiles bombed the Lviv region for the first time. So far, I have concluded that seeing refugees is the most complicated and emotionally painful thing you face during your life. Especially when those refugees are running away from the war that is going on in your country, and you cannot even assure them that the country’s region they came to is a safe place.”

15 March

Two testimonies

Anna Valchuk

Today, I want to share the testimonies of two girls I met earlier in Lviv:

Nadila, 21: "I’ve started volunteering at the Lviv railway station since the early days of the war. At the beginning of that experience, I was highly offended by any reproach, raised voices, pushing, or cursing. First days on the railway station were chaotic: both in people’s heads and on the platforms. That mess exacerbated all the feelings. I burst into tears many times for various reasons: for someone is leaving and someone has to stay; for there are those hastily rushing forward, and others humbly waiting for hours when their turn comes; some are sincerely grateful, and some think what is given to them is not enough.

What struck me most was the short dialogue with a girl my age who was leaving on the fifth day of the war.

She met me, shook my hand, and said with a friendly smile, 'Thank you for what you’re doing.'

I cried."

Diana, 19: "After my university became a shelter for students’ families from cities where hostilities occur, it was my first time I got acquainted with many refugees. Besides, many friends volunteer at various spots, including refugee centres.

Many of them join the volunteer community at the university – and that’s great!

After all, it allows going the limit, even after resuming studies and work. People are mainly relatively calm, sensible, and happy to talk. Children are primarily cheerful and active.

In my opinion, Lviv welcomes people from other regions with great dignity. Residents open many hosting places on their initiative, even in gyms, studios, etc. And many people I know personally provide shelter in their homes. Those who have a car regularly help people get from the station to the border."

14 March

Sorry for not sending new material yesterday. I will send more today. Our region had an air strike for the first time. We are okay, but it is somewhat difficult to keep my schedule going with 4+ hours in a bomb shelter. Sorry for the delay once again. – Kateryna

10 March

Maternity Hospitals and Infirmaries as Military Targets

Alina Voronina,Vira Saliieva

While Russians are claiming they only damage military targets, more and more Ukrainian civilians, including women and children, suffer from the bombings every day. The maternity hospital and the children’s hospital in Mariupol were bombed by the Russian military forces on 9 March.

At least 3 people died, with 1 child being among them. There are 17 injured people, and the obstruction removal still continues.

“How did [those hospitals] threaten the Russian Federation? Were there Bandera children there? Pregnant women were going to shoot at Rostov? Did someone in the maternity hospital humiliate Russian-speakers? What was that? Denazification of the hospital? This is already beyond atrocity," said president Volodymyr Zelensky in his speech. He also claimed that the air bomb thrown on the maternity hospital is the major act of the genocide of the Ukrainians.

Innocent people all over the country just like us, simple students, are beyond terrified with the ruthlessness of the attack. "They crossed all the borders a long time ago, and I thought that none of their actions could impress me anymore. I was wrong”, says Oleksandra Besarab. She is a second-year politics student at Ukraine Catholic University (UCU), and Mariupol takes up a special spot in her heart; she took part in the ULA course there. “A maternity hospital. I can't even get my head around it. When I was scrolling through photos and videos, I felt nothing but emptiness and pain that couldn't be expressed through words. We won't forgive. For every child who wasn't given a chance to be born and explore life. For every mother who lost the most precious gift she had. Nothing on the Earth could justify this."

No comments:

Post a Comment