From lithub.com

At its best, the relationship between novelist and reader is an intimate one. Can I tell you something? whispers the writer, and the reader whispers back, Please do… Of all the forms that the novel can take, the diary is surely the most confiding of all; it’s as if the intimacy level has been turned up to max. Can I tell you something really private; something I wouldn’t share with anyone else…?

A diary has the potential to be funny, by showcasing the idiotic lapses and random thoughts we’re all prone to, but too embarrassed to admit. It can be exciting: a piece of on-the-spot reportage from an eyewitness who was right there today and will be right there again tomorrow. It can be a supremely manipulative text, forcing the reader’s trust, on the grounds that private outpourings are aways going to be authentic. (Are they, though? And what does it mean to call any piece of writing “private”?)

These ten novels could not be more diverse—ranging from the hilarious, to the confidential, to the downright sinister—but they all have the diary format in common.

*

E.M. Delafield, The Diary of a Provincial Lady

The twee title—and, in the case of my copy, the flowery pink cover design—does this novel no favors. It’s not twee; it’s a work of dryly comic genius. The eponymous heroine is a harried housewife and would-be writer, juggling work, children and social life in a rural village, in pre-war England. Her woes are very humdrum—feeling fed up with her dowdy old clothes, for example, or failing to gel with her grumpy husband, or thinking of a witty put-down long after her snobbish visitor has left—but the provincial lady turns everything to comedy gold with her crisply observant style.

Margaret Forster, Diary of an Ordinary Woman

An overview of twentieth-century history that manages to be involving, lucid and concise: this is a tall order for any writer, but Margaret Forster does it, to great effect, in the form of a fictional diary. The “ordinary” woman in question is Millicent King, who begins writing at the age of thirteen, on the eve of the First World War, and continues through to 1995, chronicling her own personal griefs and joys alongside the great events that shook the world during that remarkable century. As a means of getting to grips with history the diary makes total sense, because it echoes the way in which we all experience the world. Shared, public occasions never exist in a vacuum; they are only ever visible through the prism of our own private concerns—and vice versa.

Alice Walker, The Color Purple

Strictly speaking, The Color Purple is an epistolary novel, but since Celie’s letters are addressed to God it seems fair to include it in this list. “Dear God” comes pretty close to “Dear Diary”, in that both forms of address imagine an idealised audience, with boundless reserves of sympathy, patience and understanding. Celie is certainly in need of a good listener; her life as an impoverished African-American teenager in rural Georgia is harsh beyond measure. Walker’s novel records Celie’s struggles against—and eventual triumph over—a society that seeks to brutalize her physically, mentally and emotionally. Whereas a third-person narrative might tend towards showing Celie’s sufferings, the “Dear God” format allows Celie to use the act of writing in order to think her way through events. Keeping a diary becomes, in itself, an assertion of will.

Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White

Perhaps the most sensational of all Victorian “sensation” novels, The Woman in White purports to be a document patched together from various sources, one of which is Marian Halcombe’s diary. Marian is an extraordinary heroine by any standards, but especially when you consider the nineteenth-century norms she’s busting: not only is she permitted to have a masculine face, complete with large jaw and nascent moustache, and to avoid being glammed-up and/or married off by the end, she is also the most intelligent, courageous, loving and resourceful character in the novel. When I read The Woman in White as a teenager, I was very jealous of Marian’s diary: unlike me, she always had something thrilling to write about (when did I ever get the chance to climb about on the roof of a stately home, in the rain, in order to eavesdrop on a pair of villains?), on top of which, her diary had the propulsive narrative structure that mine consistently lacked. Somehow, at the time, it didn’t occur to me that the contrast wasn’t my fault: real diaries can but plod from day to day; only the fictional ones can carry a tightly-honed story.

Bram Stoker, Dracula

Dracula is another Victorian novel composed entirely of letters, diaries and newspaper articles. It opens with the journal of a solicitor named Jonathan Harker as he travels to Transylvania to meet a mysterious new client, at which point events take a turn for the bloodthirsty—in an entirely literal sense. The advantage of the diary format is clear: the reader is able to watch Count Dracula’s horrific schemes unfold with a day-by-day, hour-by-hour immediacy, and from a variety of perspectives. If there’s a disadvantage, it’s in the clash between the fictional narrator’s presumed state of mind, and the actual author’s desire to write lucidly and well, with a slow ratcheting-up of tension. Within the space of a few hours, Harker finds himself imprisoned inside a gothic castle, at the mercy of a man who is able to crawl around like a bat on a perpendicular wall, and very nearly loses his life in an erotic encounter with three vampire women. Do these freakish events mess with his prose style? Not one bit. Aside from the occasional gentlemanly exclamation (“God preserve my sanity!”) Jonathan remains a diligent and cogent diarist.

Gillian Flynn, Gone Girl

[SPOILER ALERT] A secret diary is the most confessional and intimate form of writing, and therefore it’s instinctive to want to trust the diarist’s voice. Why would someone be lying when they are only writing for themselves? In Gone Girl—twistiest of thrillers—Flynn uses this intuitive trust to great effect, confusing readers into believing that they really, truly know Amy Dunne, because they’ve read her "secret" diary. Turns out they're wrong...

George and Weedon Grossmith, The Diary of a Nobody

“Why should I not publish my diary?” Charles Pooter demands, at the start of this deftly comic satire on life in 1890’s suburbia. “I have often seen reminiscences of people I have never even heard of, and I fail to see—because I do not happen to be a ‘Somebody’—why my diary should not be interesting.” Quite. When it comes to keeping a diary, there is always the potential for pomposity: what, after all, makes any of us believe that our daily thoughts and actions are sufficiently important to be placed on record? Charles Pooter is a middle-class London clerk, with worries and concerns that are far from grandiose (“Will the butcher sue me, after tripping over my boot-scraper?” “Do my ill-fitting trousers make me look like a sailor?” “Would it be a good idea to paint the bath-tub red?”), but for all his pretentions, he is oddly endearing. Perhaps it’s because he’s so recognisable. There’s a little bit of Charles Pooter in every one of us who has ever kept a diary.

Sue Townsend, The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole aged 13 ¾

Although written a century later, and purporting to be the outpourings of an adolescent boy rather than a middle-aged man, this hilarious YA novel is a close cousin to the Grossmith brothers’ Diary of a Nobody. A self-styled Intellectual with a loathing for Margaret Thatcher, a terror of acne, and a passion for Pandora Braithwaite, Adrian Mole is a wonderfully Pooter-ish mixture of pretension and lovability. Under the cover of humour, Townsend’s novel also offers a glimpse into working-class Midlands life during a difficult decade for Britain, when unemployment was rife and class division very real.

Dodie Smith, I Capture the Castle

A diary is so often a teenager’s best friend, so it’s the perfect vehicle for a coming-of-age story. I Capture the Castle may not be as laugh-out-loud funny as Adrian Mole, but it’s humorous and touching in its own quiet way. In 1930s England, Cassandra Mortmain records the ups and downs of life in a crumbling castle, where she resides with her eccentric family. Their lives are changed, for better and for worse, by the arrival of two dashing American brothers, Simon and Neil Cotton. I discovered this book when I was about fourteen—the perfect age—and fell in love from the very first line. “I write this sitting in the kitchen sink,” Cassandra tells us, engagingly. “That is, my feet are in it. The rest of me is on the draining board.”

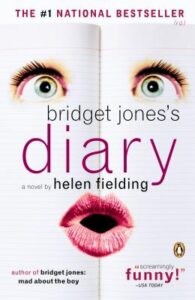

Helen Fielding, Bridget Jones’s Diary

A very 1990s take on Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and one of the defining books of the decade, it’s difficult to imagine this novel in any other format. Bridget’s insecurities, and her preoccupation with daily calorie-intake, cigarette-count and weight gained or lost, are the kinds of things a heroine can only really confide in the pages of her dairy. Fielding’s writing is so good that the plot—Bridget’s gradual disillusionment with caddish Daniel Cleaver, and growing appreciation of Mark Darcy’s true worth—seems to unfold effortlessly, in and among the hilarious descriptions of Turkey Curry buffets, Tarts and Vicars parties, and blue-string soup.

https://lithub.com/intimacy-and-manipulation-a-reading-list-of-fictional-diaries/

No comments:

Post a Comment