From vrt.be

VRT NWS journalist Tim Pauwels lives in the former home of Frans Verbelen, one of the 15,000 Belgian resistance fighters executed for their acts. He recently came into possession of the man’s letters from prison. Extracts are published here.

There were 150,000 Belgian resistance fighters during the Second World War. 15,000 of them paid with their lives. One, Frans Verbelen, wrote about his experiences from the prison in Sint-Gillis, Brussels, as he awaited his death sentence.

Verbelen had just arrived at work when he was arrested by the Germans. It was 3 April 1941. The charge: espionage.

As head guard at the Schaarbeek goods station, Verbelen kept lists of trains carrying military equipment. He thought the information could be important to the Allies. He passed the lists on to other members of the resistance, but one of his packages was intercepted.

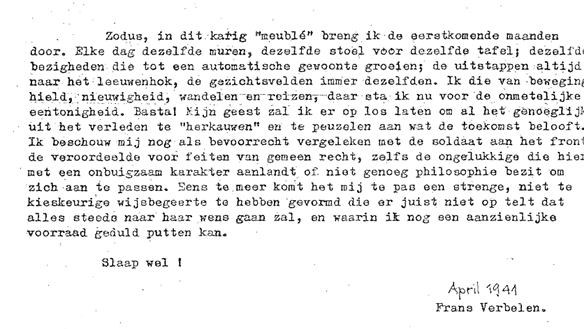

Verbelen was jailed in the prison of Sint-Gillis. From his cell, 359, a room measuring 3m x 4.5m, he wrote to his wife and three children in Evere. It wasn’t just any letter. It resembled an essay, addressed to no one in particular, 21 pages long and called “In three days around my cell”.

In it, Verbelen takes the reader into his experiences as a prisoner. He writes about his situation with a thick layer of irony: “A prison cell, full of compassion, kindness and completely unselfish, has taken me in,” even though “I lacked any particular aptitude for the vocation of prisoner. Nevertheless, as such, I have been accorded this honour.”

He does not know how long he will remain imprisoned here. His “suite”, as he calls his cell, is bare and austere: a bed, a chair, a wall cabinet, a tap with a washbasin, white walls (though no longer so white due to “stains from dead flies or crushed ants”).

Millions of bricks were needed to build this prison. He comments: “Now you can imagine the happiness of the quarry managers who landed such an order.” And then, with that same irony: “One man’s death is another man’s bread.”

Even though his movements have been reduced to this tiny cell, “the mind knows no walls”. In his mind, he is not a prisoner awaiting his death sentence but a guest in a hotel. “Accommodated, fed and served at the expense of the state – you don’t even have to tip – isn’t that wonderful!”

In these times of war and deprivation, he writes that he is better off than the people outside the prison walls, because he is “free from all worries about high prices and rationing; shelter, heating, clothing and food are guaranteed”.

Only the food leaves something to be desired. “My third evening meal here is being served. No potatoes with rutabaga this time (hurray!), now it’s rutabaga with potatoes.”

He comments on the food served to him, like a critic reviewing a restaurant. “It will probably be unnecessary to wait for the next courses, to point out to the maître d’hôtel a fly floating around my soup or to draw his attention to the scarcity of meat.”

There is also room for improvement in terms of hygiene: “By the way, you can see everything on those walls! There’s even a spider web. When the valet comes to make my bed, I’ll point it out to him. They should know that I like cleanliness here!”

When evening falls, his thoughts turn to his home, wife and children. “It’s not pleasant to think about what a shock it must have been for my family to learn that I have been taken out of circulation for the time being.”

He is particularly concerned about his children: “They haven’t outgrown their childhood, it was ripped from their feet.” He writes home: an activity that gives him strength, but which he finds difficult.

“It always weighs heavily on my heart, but it is also really pleasant. I feel united with my loved ones; no distance or obstacle separates us. I cheer them on and they encourage me; we leave sad thoughts behind and make plans for the future.”

He describes loneliness as the hardest part of his imprisonment. That loneliness is accompanied by boredom. He sits alone in his cell for hours, watching the sun slowly move across the wall. After just three days, it feels like he has been there forever.

Nevertheless, his letter ends on a hopeful note: “I will let my mind wander, ‘chewing over’ all the pleasant things from the past and savouring what the future promises.”

This letter came to our newsroom via the Kortenberg Heritage Centre. The editors tried to trace Frans Verbelen’s descendants without success. If they wish, relatives can contact us at nieuws@vrt.be.

'I am not afraid of death'

On 28 June 1942, Frans Verbelen was executed by firing squad. He was shot in Tegel, a district of Berlin. He is said to have gone to his death calmly. Half an hour before his death, he picked up his pen one last time.

He said goodbye to his children and asked his wife for forgiveness. By refusing to reveal the name of the person for whom his information was intended, he denied himself the chance of a lighter sentence.

“Dear wife, you are the victim of my attitude,” he wrote. “Forgive me, my beloved, for all I have done to you and caused you to suffer. Be brave, my dearest treasure. Show that you can forget your suffering, so that you may think of the children.”

Frans Verbelen was cremated. His ashes were scattered in Döberitz, not far from Berlin.

Archive network Archiefpunt is collecting diaries and other personal writings from the Second World War for digitisation and publication. Anyone can submit diaries, scrapbooks, poetry albums or letters from the period 1939-1949 for digitisation and publication via the Archiefpunt website

No comments:

Post a Comment